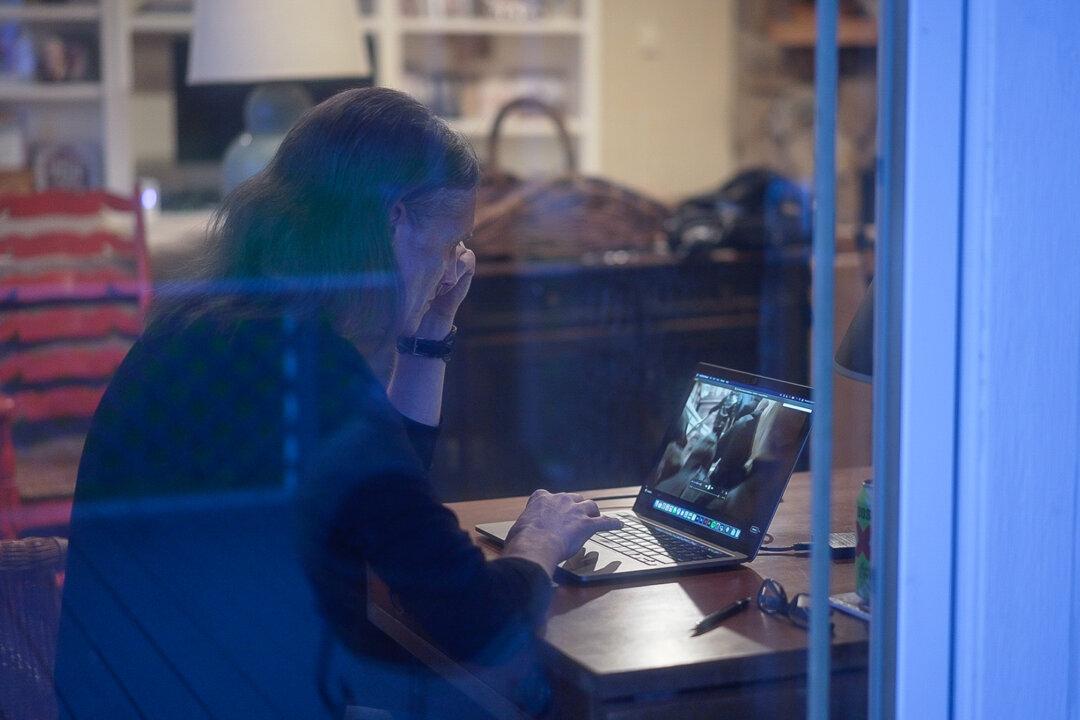

DALLAS—After a 30-hour stint investigating the minutest details of Jan. 6, 2021, video evidence, Gary McBride had to take a break for some sleep.

McBride often fights off sleep when he gets engrossed in his detailed analysis of thousands of hours of video footage from the unrest at the U.S. Capitol. To say he’s focused would be a vast understatement. Passionate, even obsessed, would be more accurate terms.