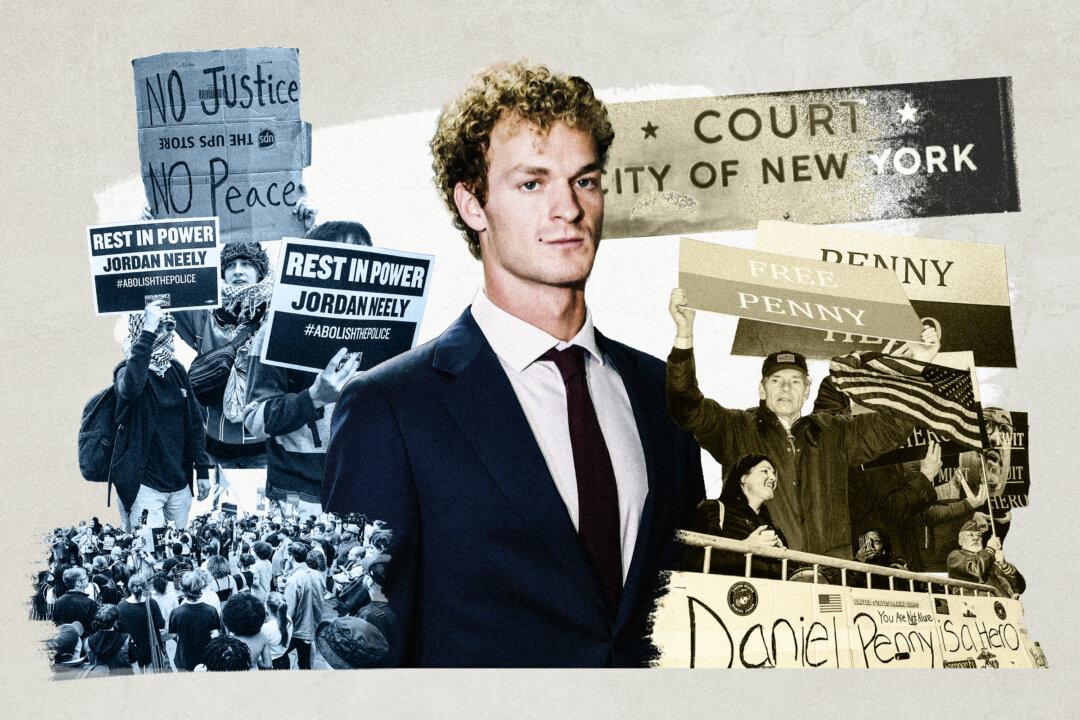

NEW YORK—A witness in the trial of Daniel Penny, a former U.S. Marine who is facing charges of manslaughter and criminally negligent homicide related to the death of Jordan Neely, took the stand on Nov. 12 to describe how he helped restrain Neely at the scene, and how he had initially lied to investigators out of fear that he might be held liable for the man’s death.

Eric Gonzalez, a 39-year-old groom manager at a casino, who spent his early years in the Dominican Republic before moving to New York, said he rides the subway every day.