The Wisconsin Supreme Court has stated that it will decide on the legality of mobile voting sites after a circuit judge ruled in January that the city’s use of a mobile van for absentee voting violated state law.

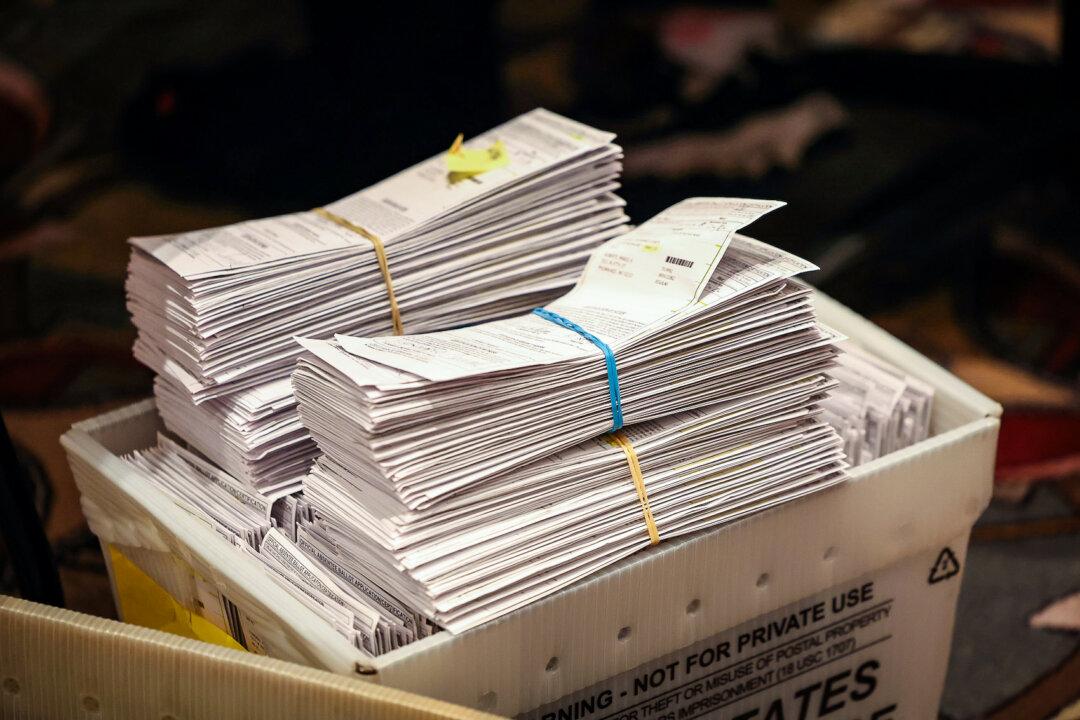

This stems from a lawsuit filed by the Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, a nonprofit conservative law firm, on behalf of Racine County Republican Party Chairman Ken Brown following the 2022 primary.