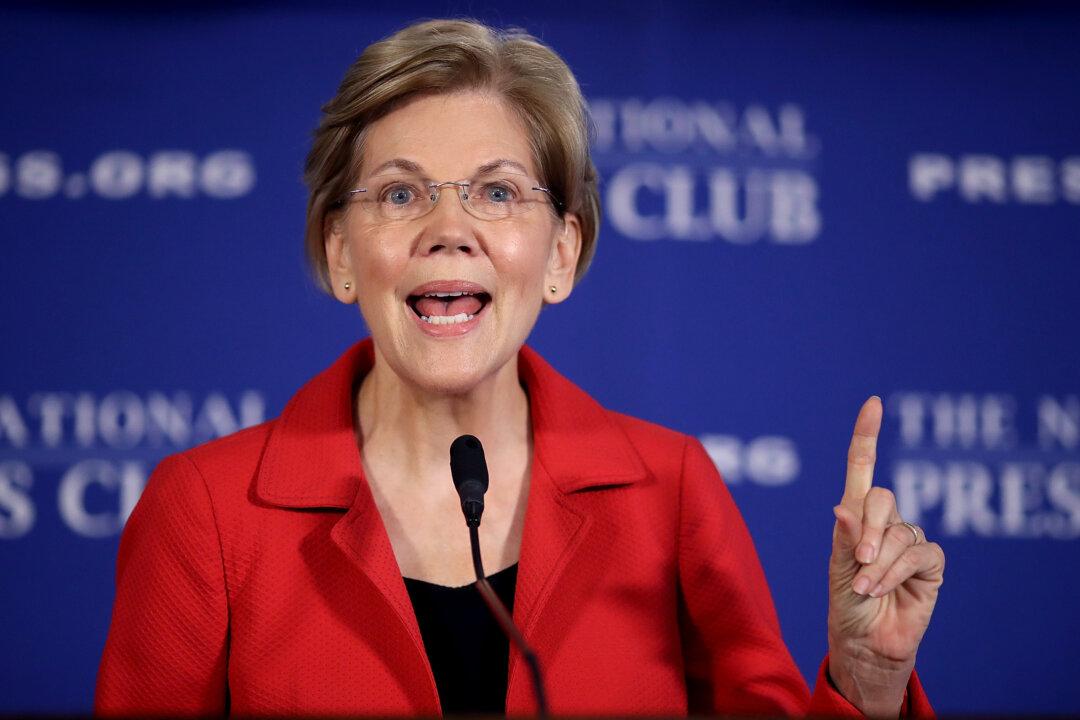

WASHINGTON—Giant U.S. corporations deliver substantial returns to their investors, thanks to the shareholder value thinking that has dominated the business world over the past few decades. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they have done well in protecting American interests, says Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.).

She introduced in August the Accountable Capitalism Act, which seeks to reverse the notion that the principle of “maximizing shareholder value” is the best way to ensure good corporate governance.