BALTIMORE—Several Roman Catholic bishops on Nov. 13 urged colleagues at their national meeting to take some sort of action on the clergy sex abuse crisis despite a Vatican order to delay voting on key proposals.

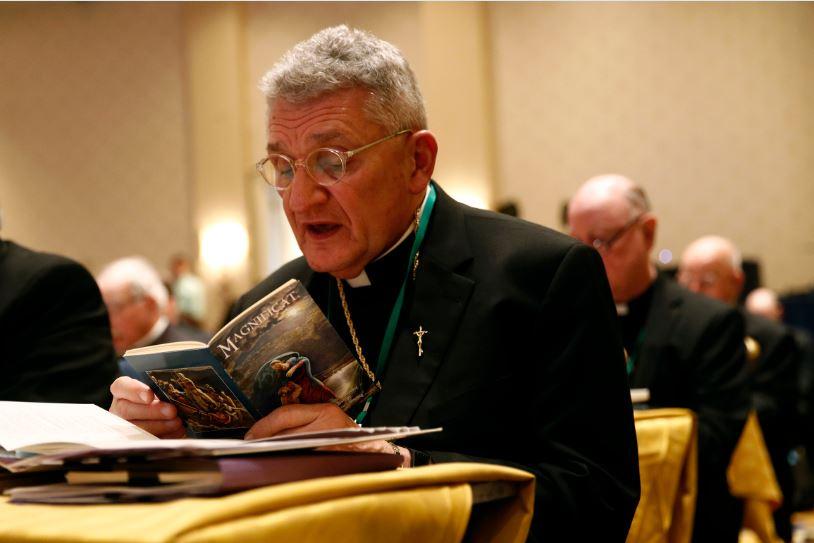

Bishop Thomas Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois, suggested a nonbinding vote to convey a sense of the bishops’ aspirations regarding anti-abuse efforts.