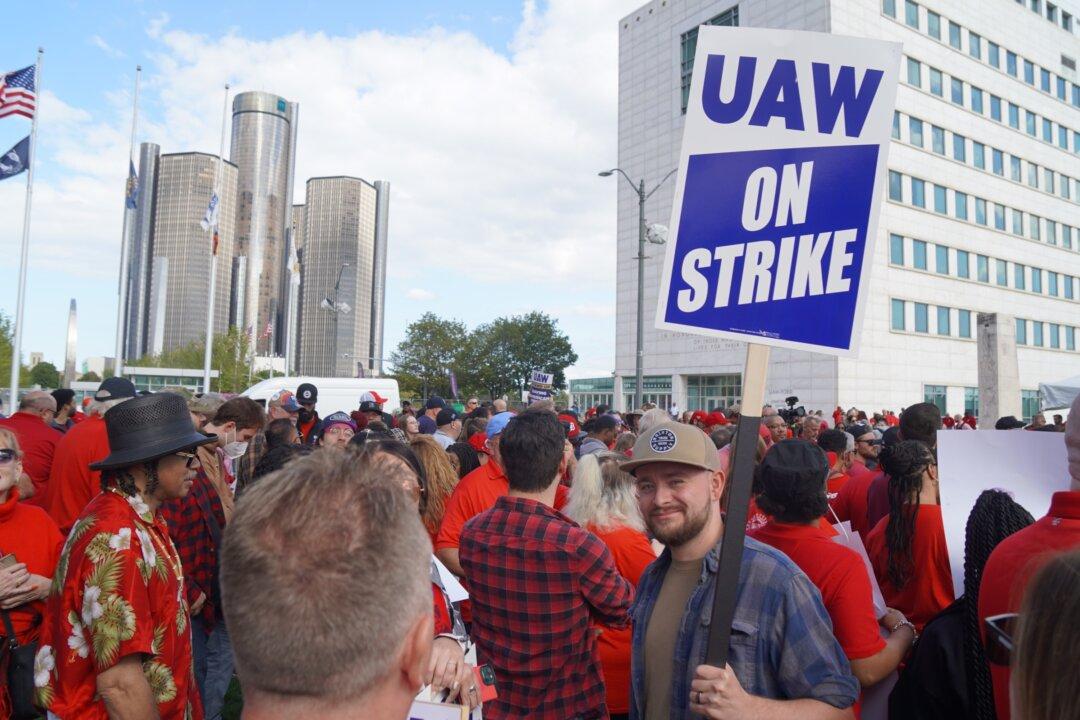

As the United Auto Workers (UAW) strike entered day 5 on Sept. 19, negotiators for the union and the Big Three automakers remained at an impasse as failed weekend talks bled into the workweek.

The two sides are apparently far apart, leading to analysts’ predictions for a long-lasting deadlock as well as experts warning that the union’s demands would make the automakers less productive and competitive than their nonunion rivals.