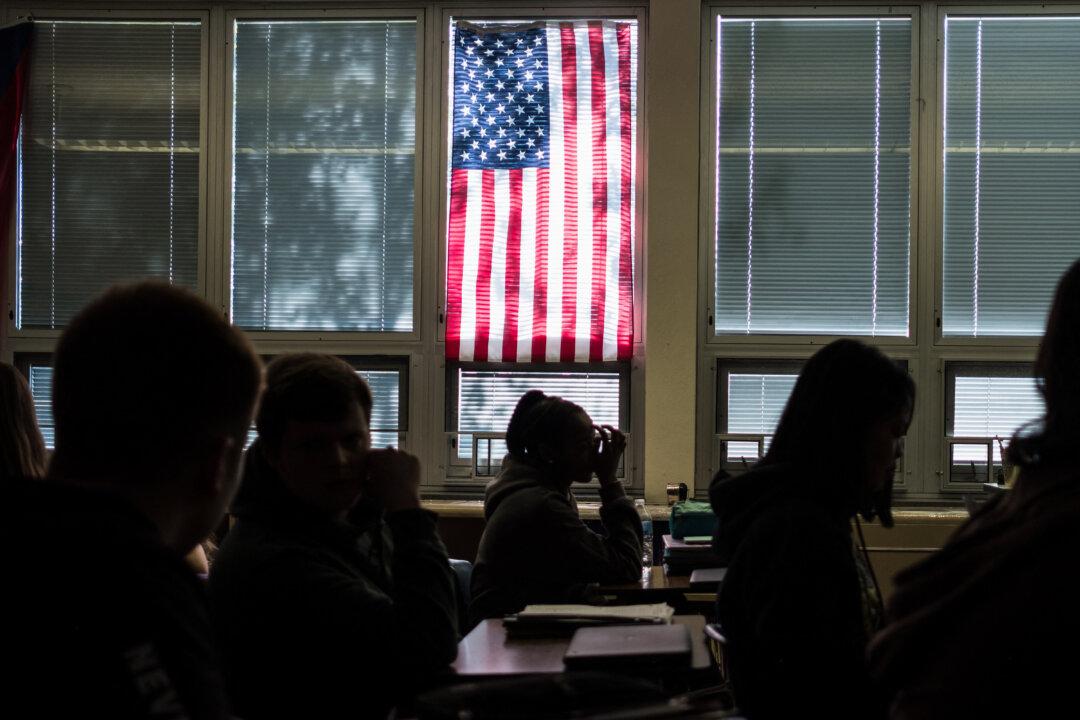

America’s education crisis is approaching another crossroads this year. Between January and July, more than a quarter of a million teachers and support staff called it quits amid heavier workloads and growing class sizes.

Complicating this is the growing number of illegal immigrant and special-needs students entering U.S. classrooms.