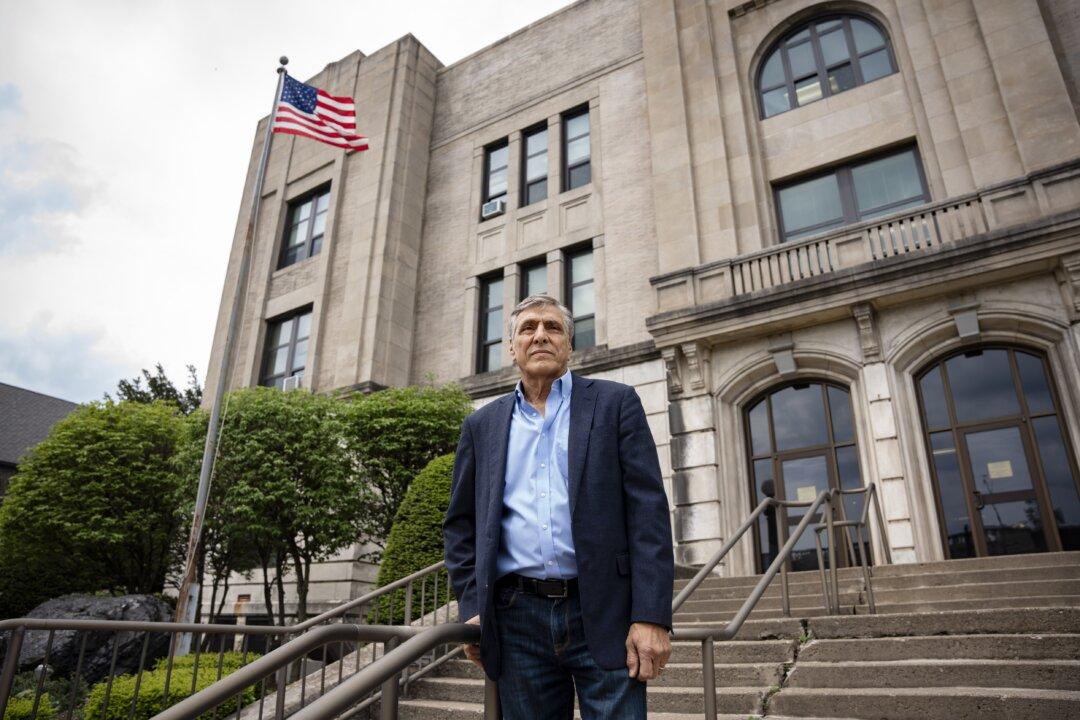

HAZLETON, Pa.—Armored with a bulletproof vest and feisty Italian determination, Mayor Lou Barletta made his way past hundreds of dueling protesters, past rows of state police mounted on horseback, and into City Hall.

It was July 13, 2006, and the Art Moderne-style building was overflowing with spectators and teeming with news reporters, Mr. Barletta said. The mayor, then 50 years old, was beholding a spectacle unlike any he had seen in his eastern Pennsylvania hometown.