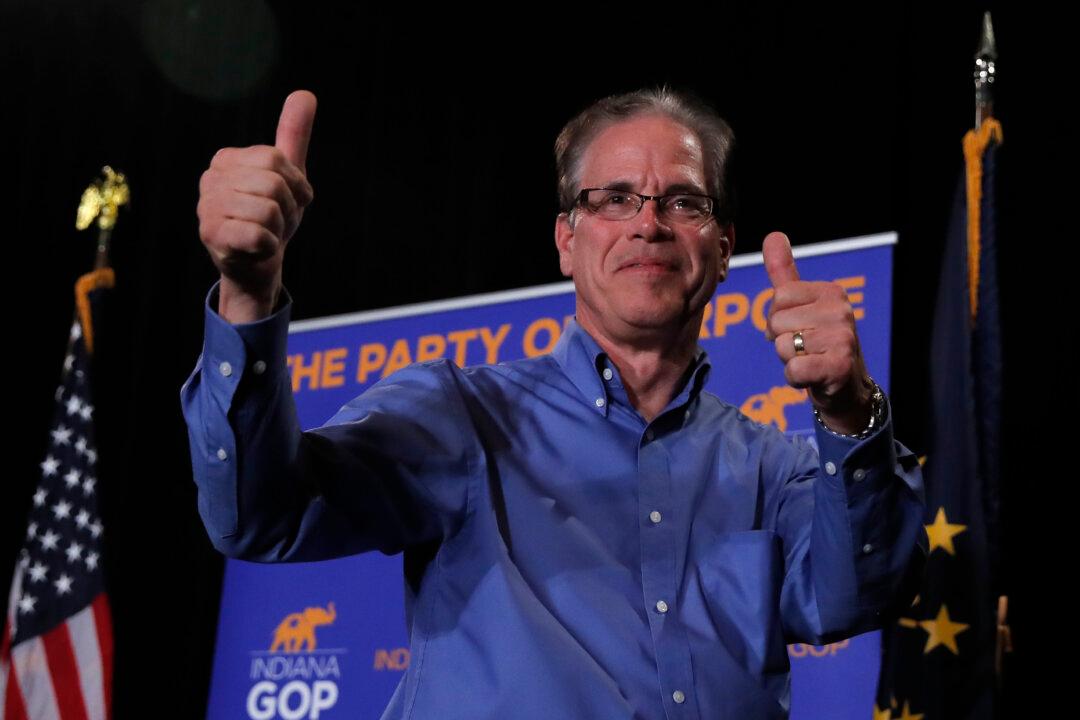

WASHINGTON—Generous tax-funded pensions for members of Congress would be abolished under a proposal introduced in the Senate on Feb. 12 by two Republican freshmen senators, Mike Braun (R-Ind.) and Rick Scott (R-Fla.).

“It’s time we make Washington more like the private sector and the best place to start is to end taxpayer-funded pensions—like Nancy Pelosi’s six-figure annual pension—that senators and congressmen are entitled to in retirement,” Braun said in a joint news release.