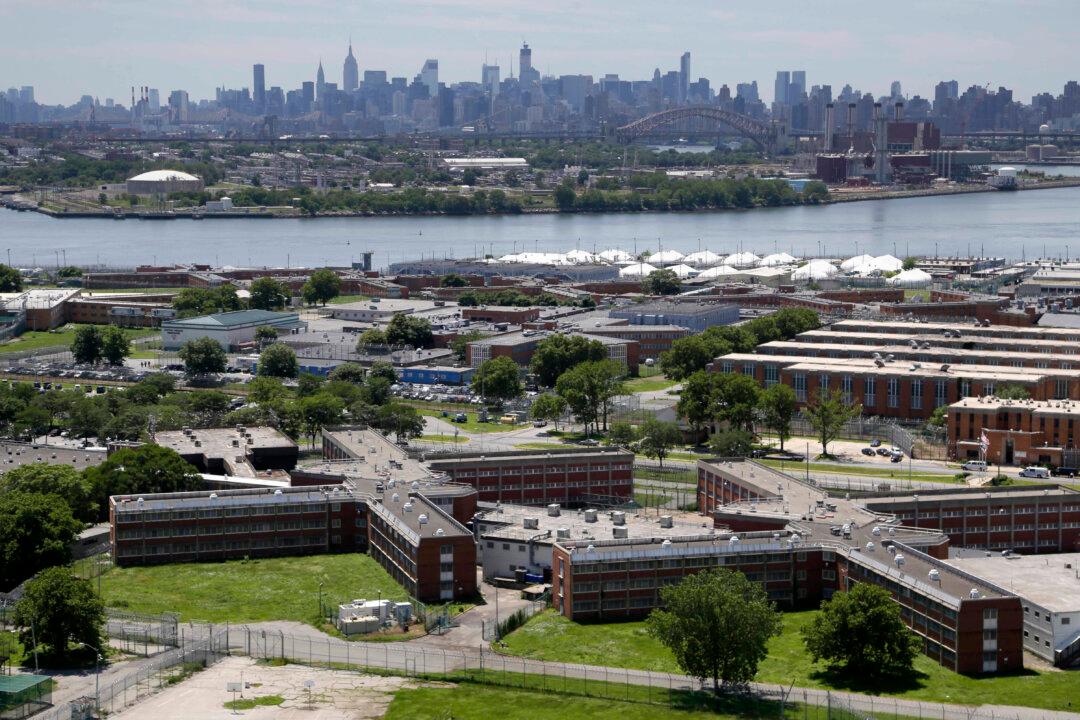

The beleaguered New York City jail on Rikers Island has slipped to the edge of utter chaos due to staffing shortages, poor conditions, and restrictions placed on guards. The city is scrambling to bring in more officers, reduce inmate population, speed up repairs, and clamp down on officers who fail to show up for work.

The large jail complex on a small island in the East River has been criticized over disrepair and bad conditions for decades, but the situation has deteriorated further over the past few years. Fights, suicides, and attacks on guards have surged. Ten inmates have died so far this year. Drugs, cell phones, and even “wild parties” have been reported, with overworked staff sometimes unable to keep order.