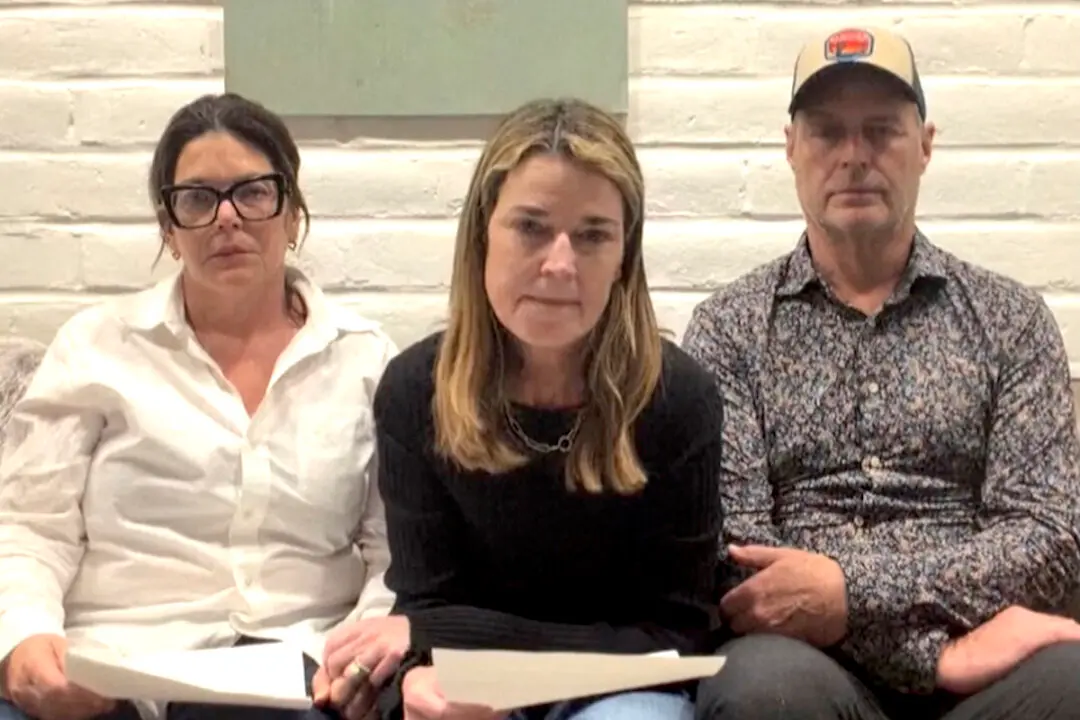

The illegal growing of marijuana in Northern California, even as the state legalized the drug for personal use less than a decade ago, continues to be of concern to some law enforcement agencies who say cartel-run cannabis farms are one of the main threats to public safety.

In Mendocino County, home to 90,000 residents and more than 3,500 square miles, as many as 4,000 to 5,000 illegal cannabis sites this year alone have been recorded, according to local Sheriff Matt Kendall.