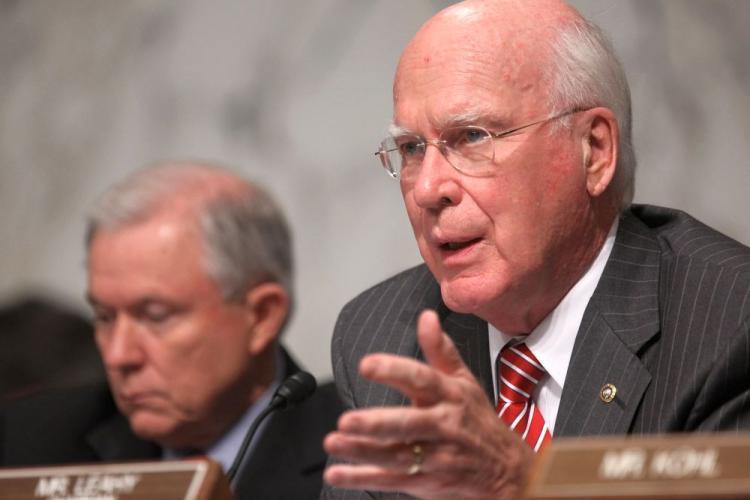

Sens. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) are asking the Trump administration to provide information on whether and how it has ended surveillance programs authorized under several provisions of a federal intelligence law that have since expired.

Leahy and Lee wrote to Attorney General William Barr and Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe on Tuesday raising their concerns that the departments may still be continuing their surveillance activities by relying on Executive Order 12333 after three surveillance tools under the USA Freedom Act, a 2015 intelligence law, expired in March.