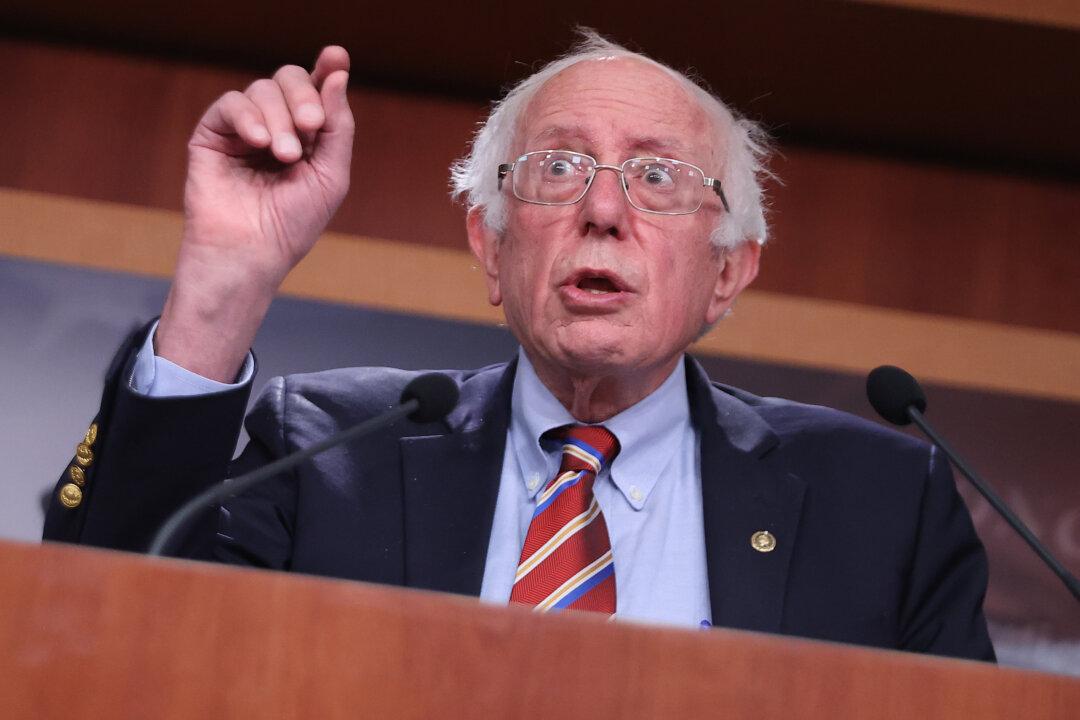

Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-Vt.) said it’s obvious America has a problem when it comes to health care.

“Simply put ... a significant percentage of our population live in places where they cannot access the health care they desperately need,” Sanders said as he opened a hearing by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) committee on Feb. 16.