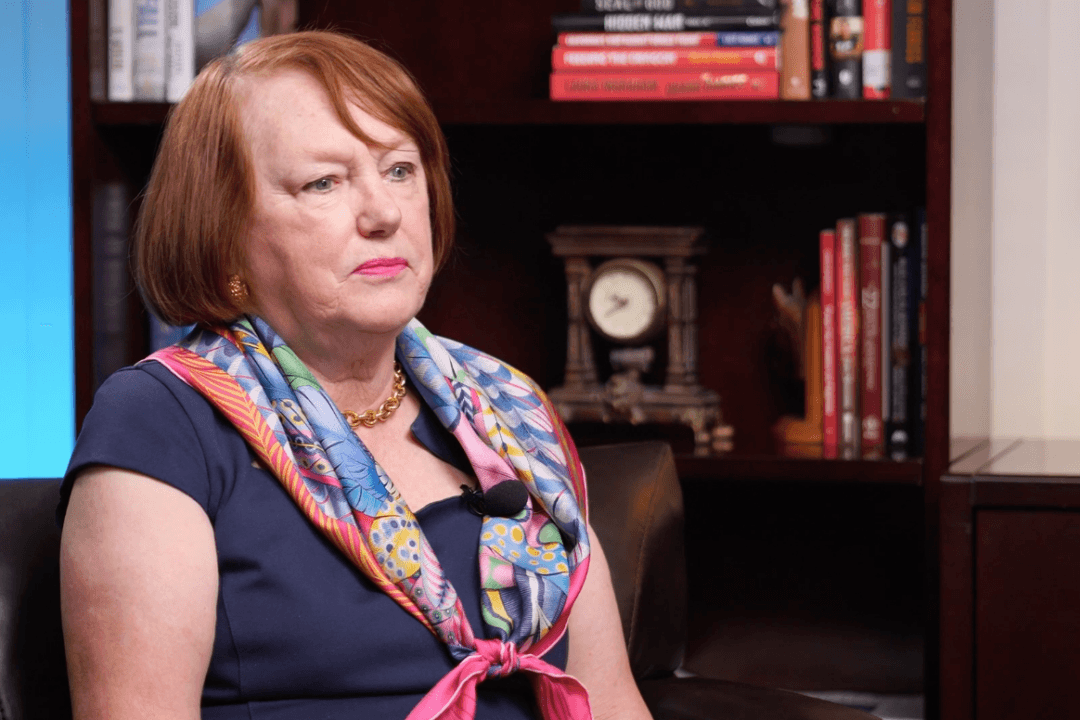

Fentanyl-dealing that results in death should be charged as homicide, on top of drug trafficking, a district attorney told the EpochTV’s “California Insider” program, where he explained the danger of fentanyl and what his office is doing to fight the deadly opioid crisis originating from “pure greed.”

“The dealers are not trying to kill their clients. They just don’t care if they do,” said Michael Hestrin, the Riverside County District Attorney. “That’s kind of a murder.”