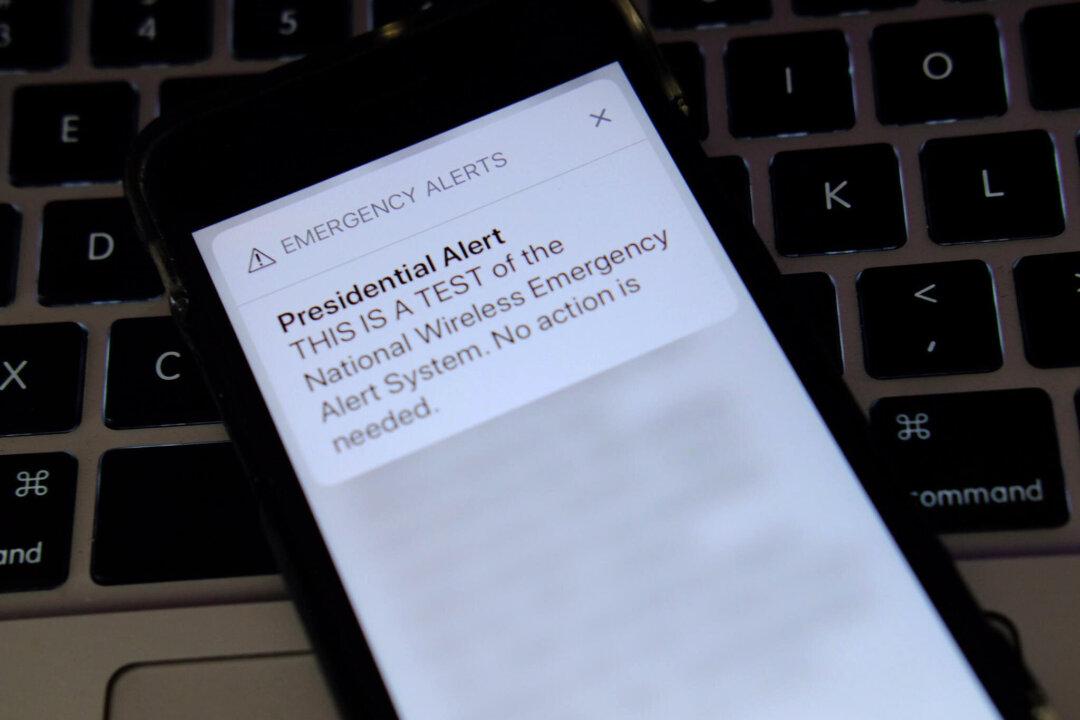

A “presidential alert” was sent out at about 2:18 p.m. ET on Oct. 4 to test a national emergency system, causing cellular phones, televisions, and radios to emit the familiar alarm sound.

“THIS IS A TEST of the National Wireless Emergency Alert System,” it said. “The purpose is to maintain and improve alert and warning capabilities at the federal, state, local, tribal, and territorial levels and to evaluate the nation’s public alert and warning capabilities.”