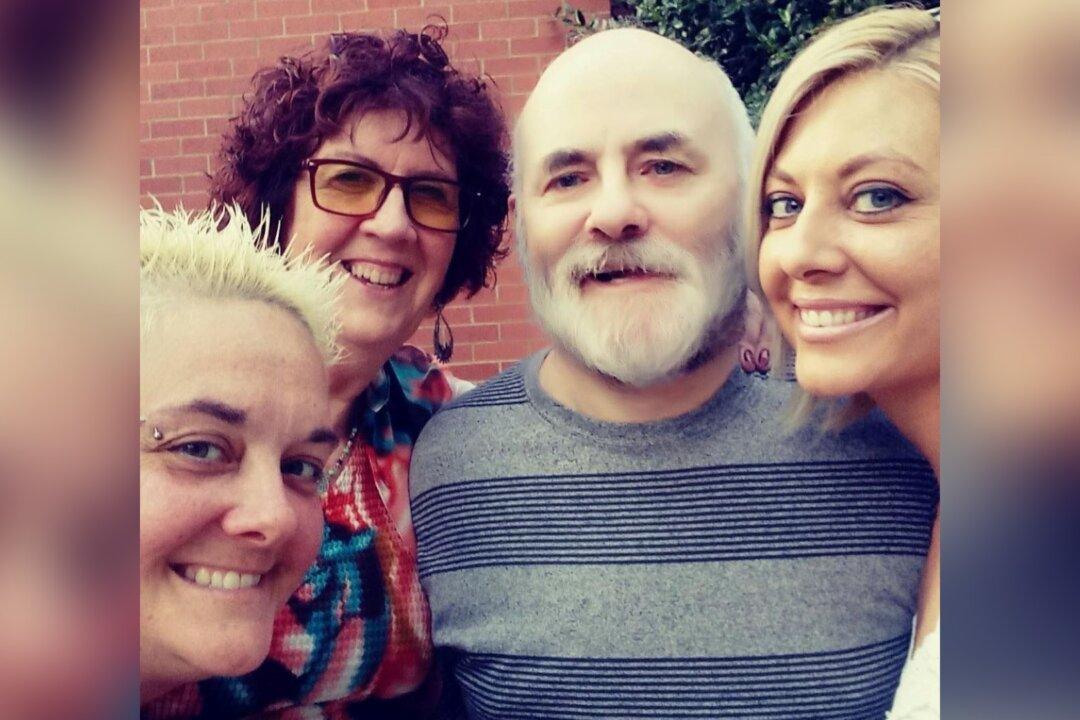

In sickness and health, Monica Seville has spent much of her marriage advocating for her husband, Gregory Seville, 62, who was diagnosed in 2005 with Huntington’s disease (HD).

Now the McConnellsburg, Pennsylvania, woman is trying to prevent her husband from being moved from a hospital 20 minutes from her house to a New Jersey long-term care facility four hours away—an eight-hour round trip. She has been told there is no long-term facility in all of Pennsylvania that will take him, and if she doesn’t agree to move him to New Jersey soon, the hospital threatens to seek guardianship so they can move him without her consent.