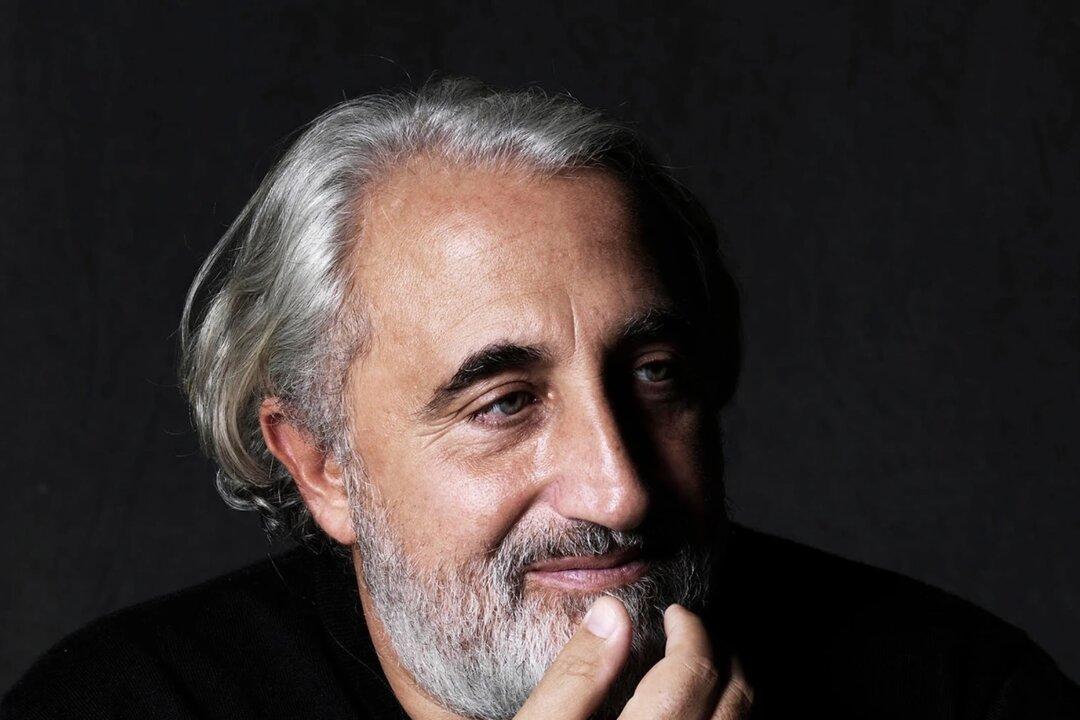

“It takes professors to come up with some of the dumbest ideas,” says Gad Saad, a Lebanese-Canadian professor of marketing at Concordia University and author of “The Parasitic Mind: How Infectious Ideas Are Killing Common Sense.”

“The fact that you are educated doesn’t mean you have properly administered the mind vaccine against all these idea pathogens.”