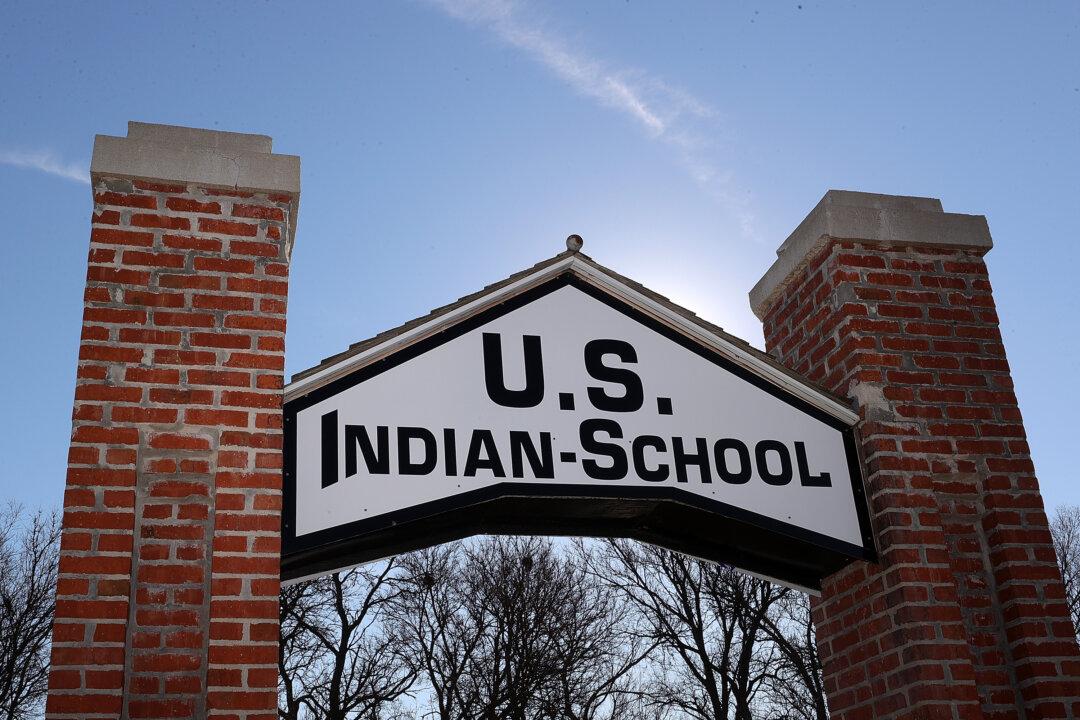

An investigative report by the U.S. Department of Interior found that more than 970 Native American children died at federal Indian boarding schools between 1819 and 1969.

At least 973 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children died while attending schools operated or supported by the federal government over the 150-year period, according to the report released on July 30.