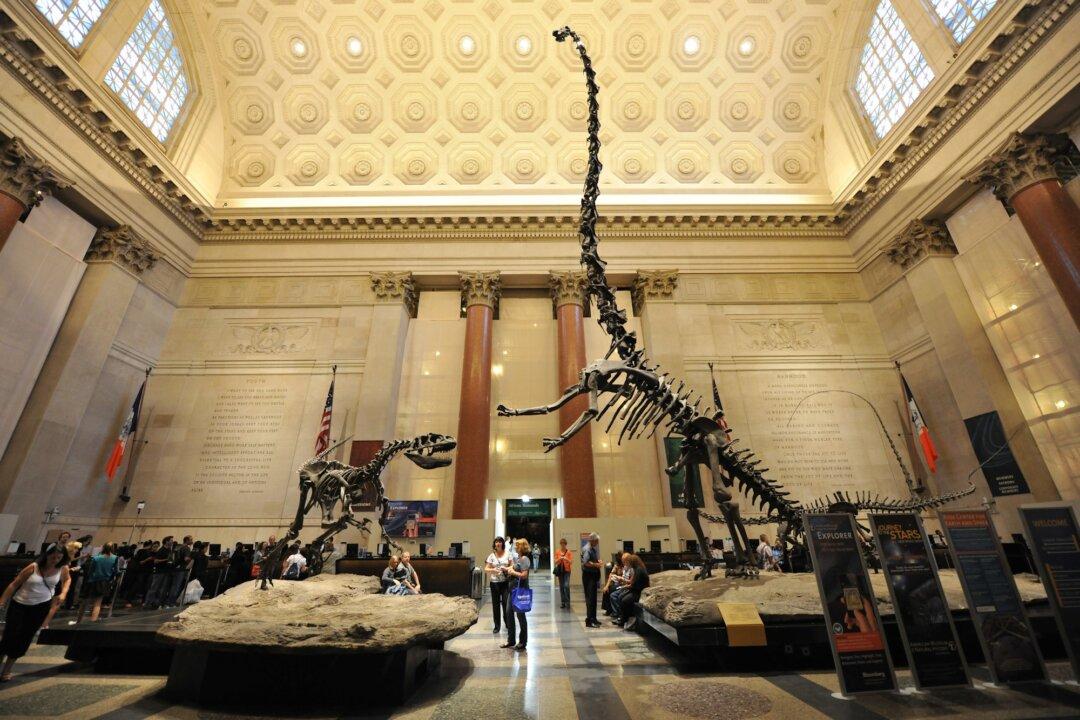

On Friday, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City emptied two of its exhibition halls and covered up multiple displays, following new federal regulations that require institutions to first obtain consent from native tribes before displaying their cultural artifacts.

The museum, which draws nearly 5 million visitors each year, said in a notice to staff members that it will close displays dedicated to the Eastern Woodlands and the Great Plains tribes for the upcoming weekend.