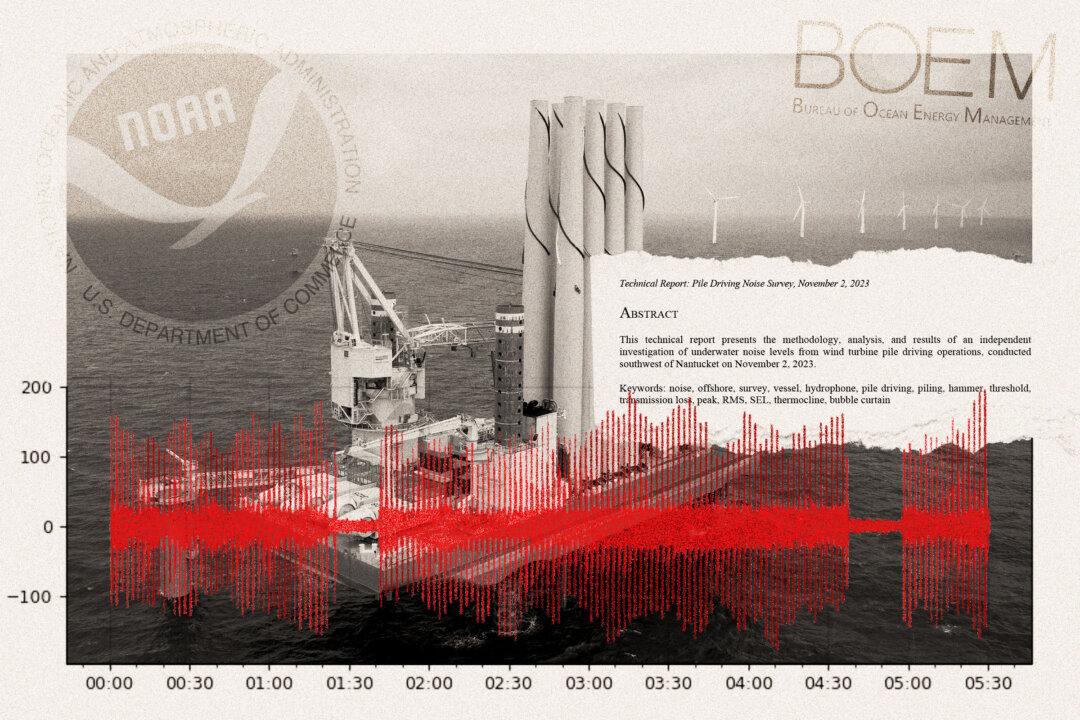

Imagine living amid noise as loud as a rock concert, all day, every day. Environmentalists say that’s exactly what will happen to all sea creatures—from fish to whales to clams—in the waters around the massive offshore wind farms planned for the eastern coast of the United States.

The spinning windmills will be so loud, they say, that people at the beach will hear them, too.