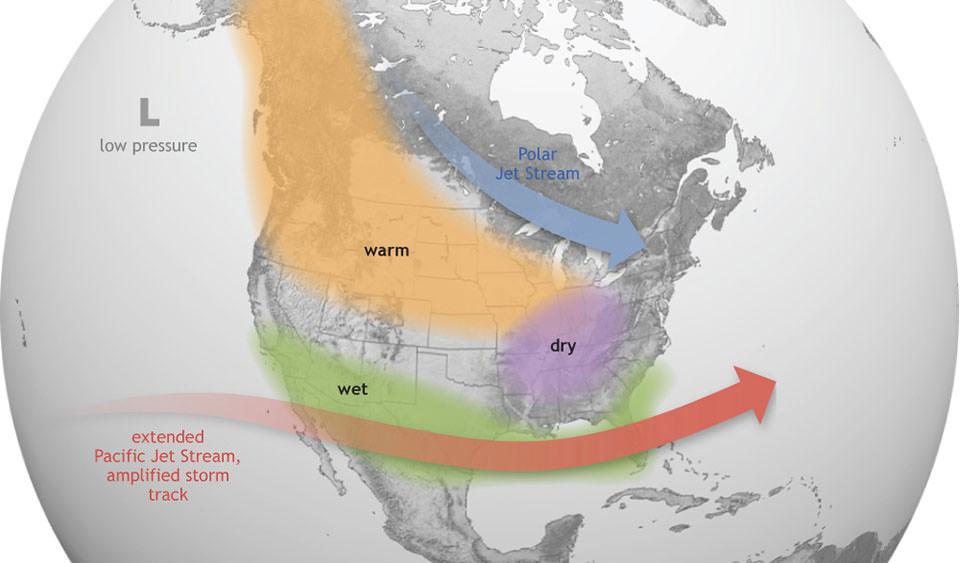

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has declared the arrival of El Nino, an on-and-off-again weather phenomenon that brings warmer sea temperatures near the equator.

The agency noted that El Nino occurs every two to seven years, on average, and it can bring heavier rain to some parts of the world or drought in others. On its website, NOAA said that the weather phenomenon was expected to come, saying that it will be “moderate-to-strong” by the fall and winter months.