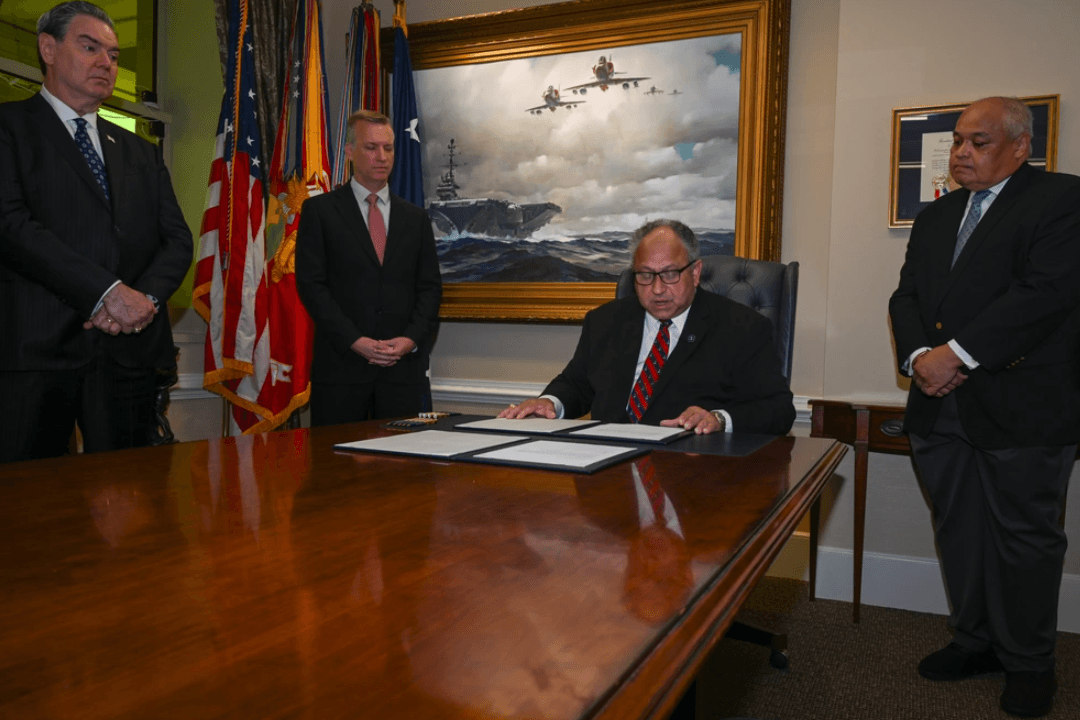

Secretary of the Navy, Carlos Del Toro, announced on July 17 the full exoneration of 256 black sailors who had been convicted in trials by court-martial for refusing to handle ammunition after a deadly explosion at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine in California 80 years ago.

On July 17, 1944, 320 people were killed and around 400 injured in an explosion that took place while sailors were loading ammunition onto a cargo ship bound for the Pacific Theater of World War II. After the incident, 258 black sailors defied orders to resume work amid concerns about continued poor safety standards; all were convicted in military trials.