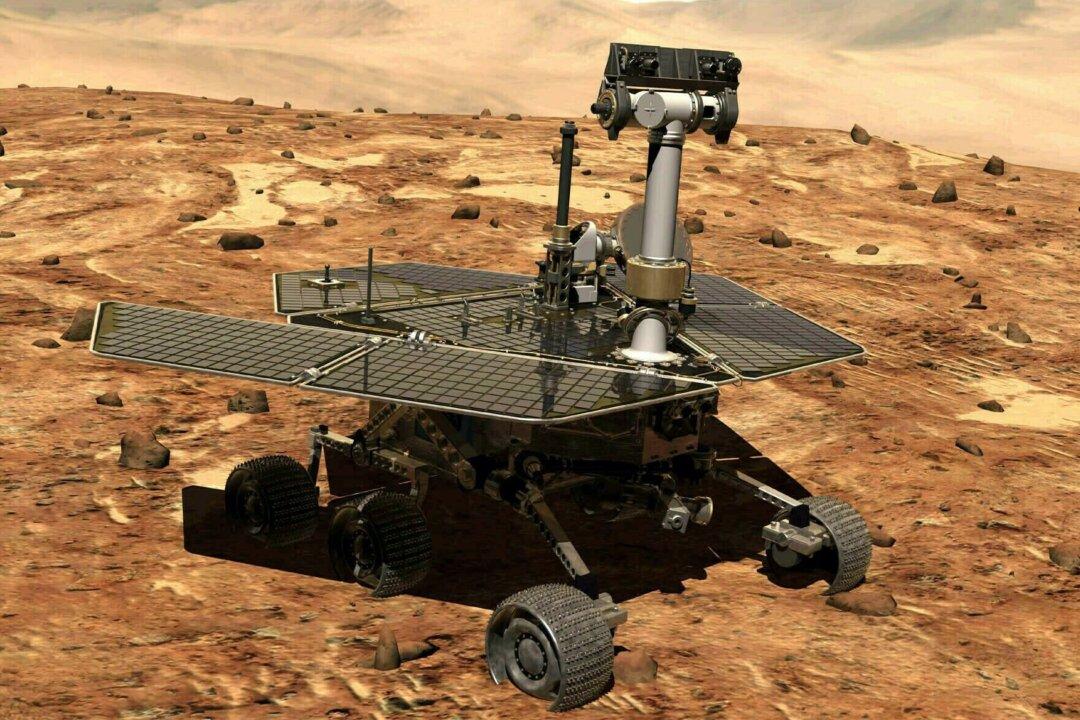

NASA is trying one last time to contact its record-setting Mars rover Opportunity, before calling it quits.

The rover has been silent for eight months, victim of one of the amost intense dust storms in decades. Thick dust darkened the sky last summer and, for months, blocked sunlight from the spacecraft’s solar panels.