It’s one thing for those with physical challenges to be told, “You can do it,” and quite another to have a living, breathing example of achievement standing before you, showing you that anything is possible.

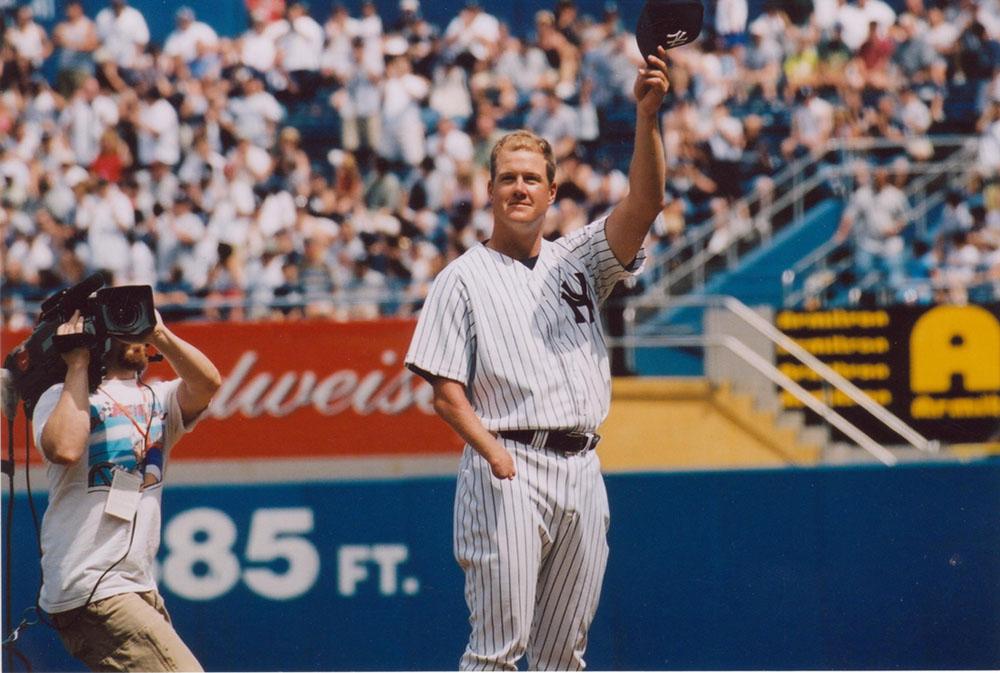

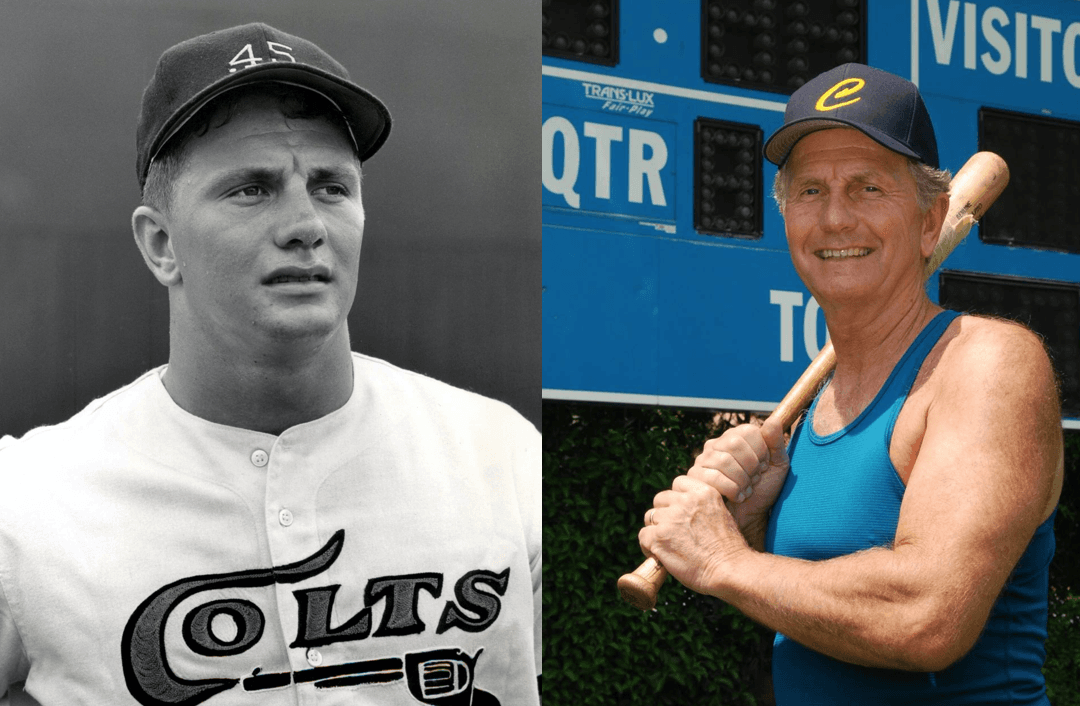

Jim Abbott has been—and continues to be—that living, breathing example to many who otherwise might have not have believed they could overcome any obstacle that life threw at them.