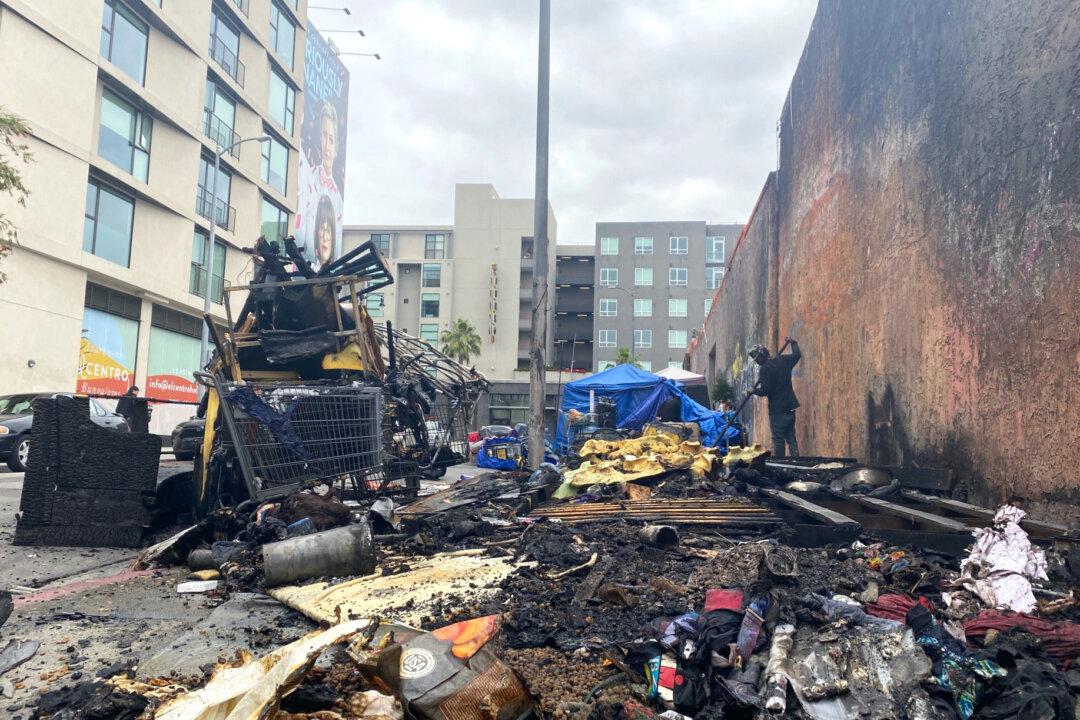

LOS ANGELES—It started with one street in Hollywood. A retiree began chatting with a neighbor who was picking up trash and volunteered to help.

Keith Johnson had spent years as a high school photography teacher. Now, looking around at what he saw as a humanitarian catastrophe unfolding in front of him, he thought the homeless crisis wasn’t being accurately reflected in media coverage—or official responses coming from City Hall.