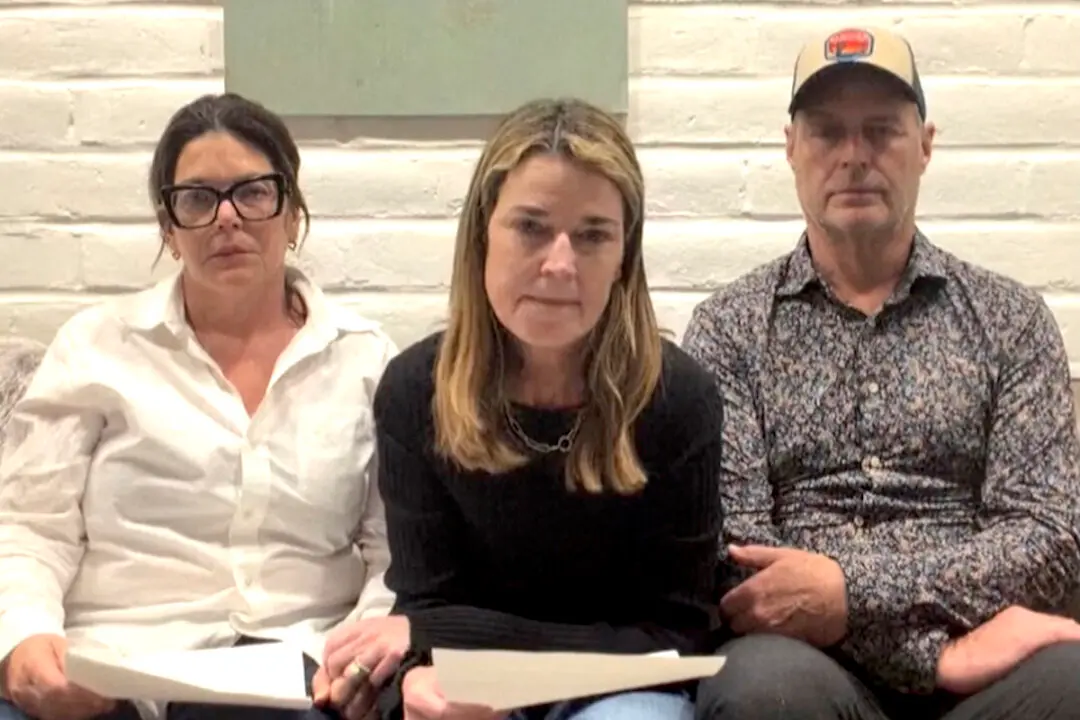

In a battle between local and state control over building affordable housing, Huntington Beach, California, is challenging the state’s housing department over a mandated plan for such and a recent court ruling sided with the beachside city.

San Diego Superior Court Judge Katherine Bacal, after the suit was transferred from Orange County Superior Court in July, ruled in favor of Huntington Beach Nov. 2, determining that it should have its case against the state heard first in federal court, despite state officials first seeking penalties against the city in state court.