When Seattle’s City Council voted unanimously to cut millions of dollars from its police budget amid the uproar over the murder of George Floyd, it ran into an unlikely roadblock: the federal government. U.S. District Judge James Robart ruled that the city couldn’t defund its own police department without his permission.

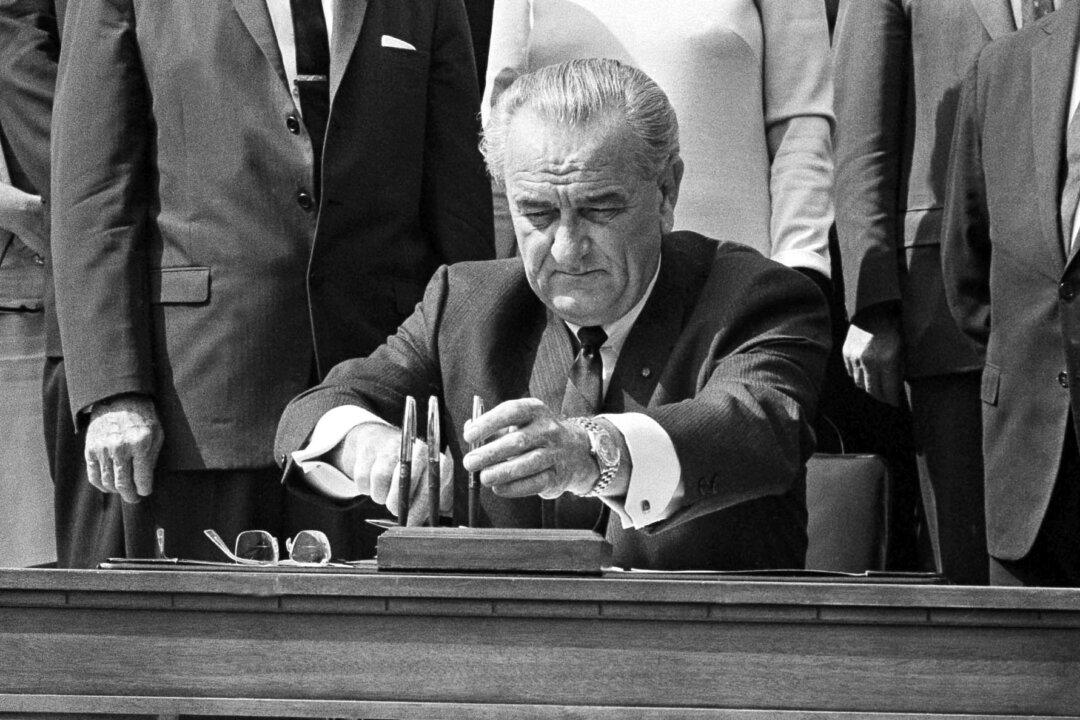

The judge was acting under the mandate granted him by a 2012 consent decree (pdf) put in place after John T. Williams, a native American woodcarver, was shot four times by a Seattle police officer in 2010. The killing was ruled unjustified. The consent decree—a sort of civil plea bargain—was one of several with police departments across the country arranged under pressure from the Obama Justice Department as it sought to end alleged civil rights abuses by police in cities from Baltimore to Cleveland to Ferguson, Mo.