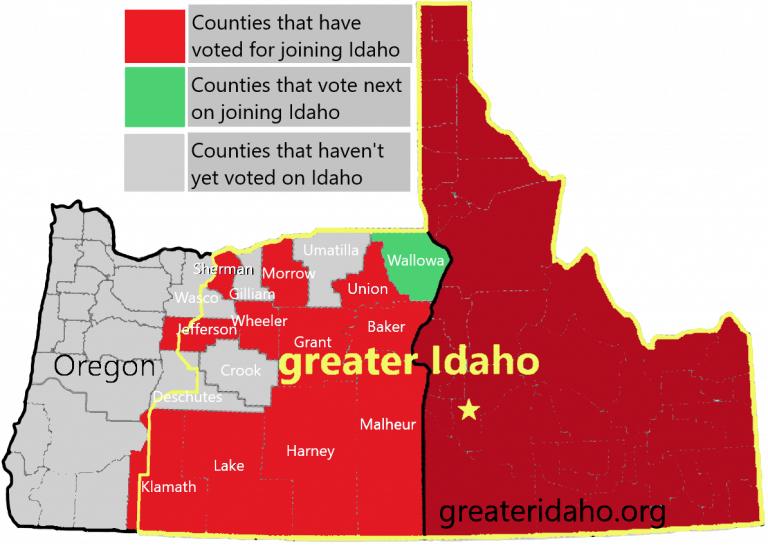

Two more conservative-leaning counties in eastern Oregon, and one politically split county in California, have voted to begin the process that could lead to secession from their respective blue states.

On Nov. 8, Oregon’s Morrow County passed the Greater Idaho proposal with 61 percent of the vote and Wheeler County with 59 percent.