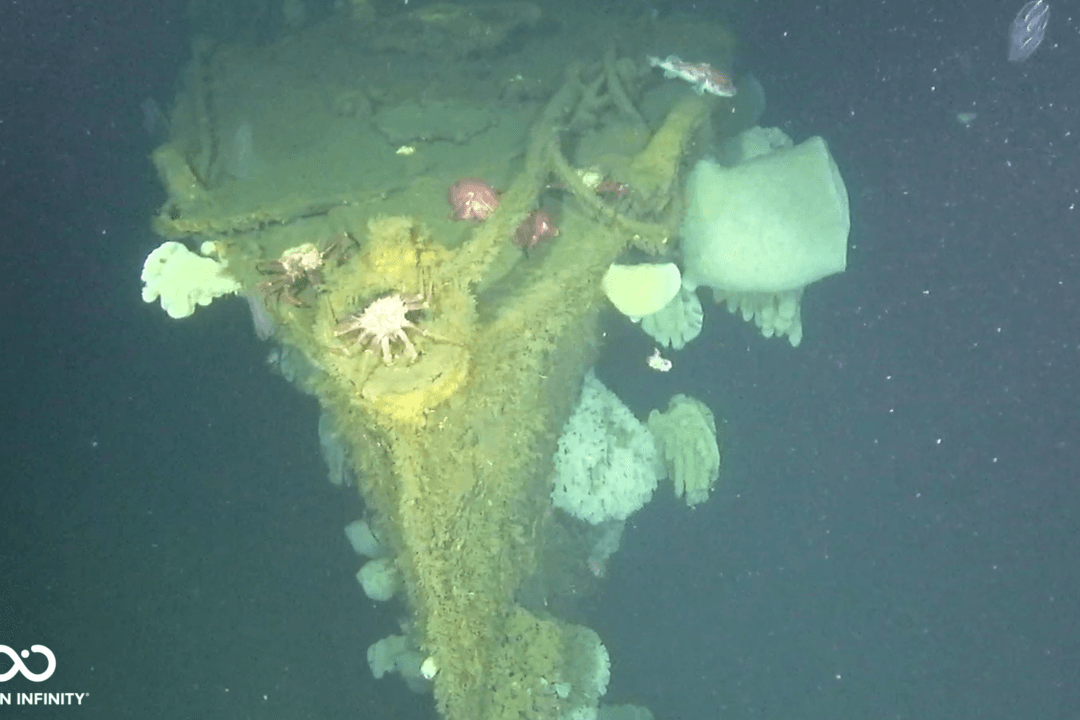

A U.S. Navy warship that fell into enemy hands during World War II, got a Japanese makeover, and became known as the “Ghost Ship of the Pacific” has been discovered off Northern California.

Locating the wreck of the USS Stewart was a collaborative effort to test the robotic marine survey technology of the Ocean Infinity company of Austin, Texas.