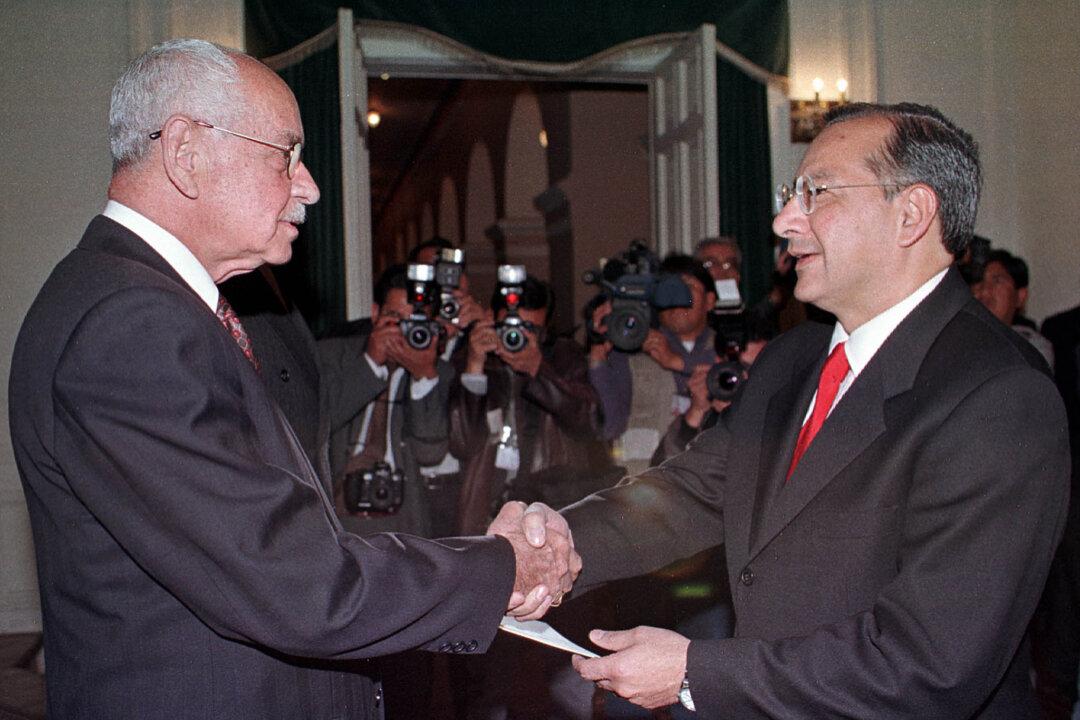

A former diplomat who once served as U.S. ambassador to Bolivia awaits sentencing in a sensational espionage trial that has made headlines since his arrest in December. Victor Manuel Rocha, 73, is accused of spying for Cuba for over 40 years. He pleaded guilty last month to two charges of conspiring to act as an agent of a foreign government; he will be sentenced at a hearing on April 12.

U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland described the case as one of the most significant and longest-running infiltrations of the U.S. government by a foreign agent in the nation’s history.