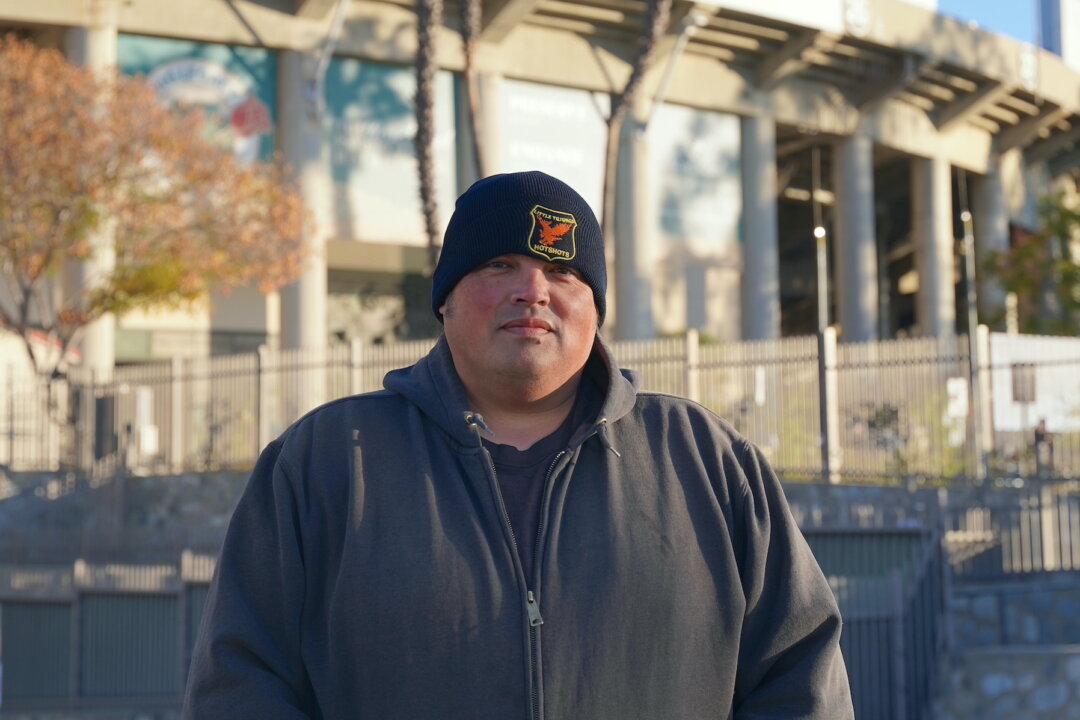

PASADENA, Calif.—On a recent frigid morning, more than a thousand first responders gathered at the Rose Bowl stadium for a daily briefing before heading out to battle a fire that has decimated nearby communities at the edge of the Los Angeles National Forest.

The stadium grounds are now a central command for fire crews from all over the Western region, as well as the law enforcement and military personnel that are stationed throughout evacuation zones.