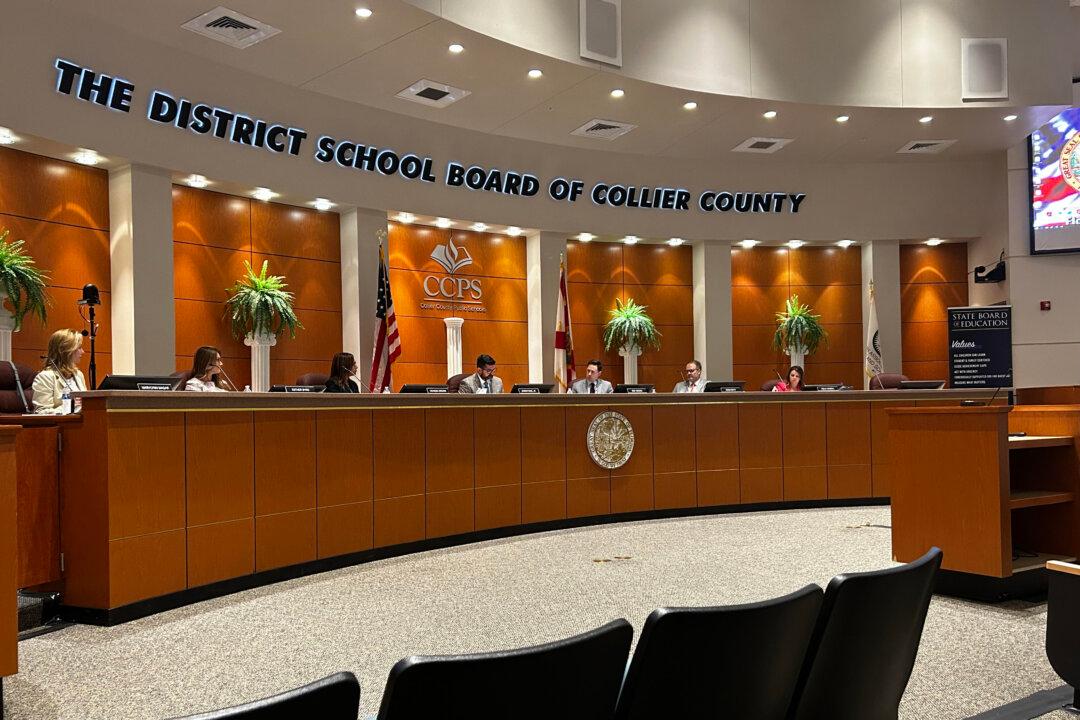

Florida’s high school graduation rate climbed to an all-time high of 88 percent in the 2022–2023 school year, during a period that some educators fear is rampant grade inflation.

The Florida Department of Education (FLDOE) tracked a 1.1 percent increase from the previous recording-breaking year in 2018–2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic, when graduating classes were exempt from certain statewide standardized testing requirements.