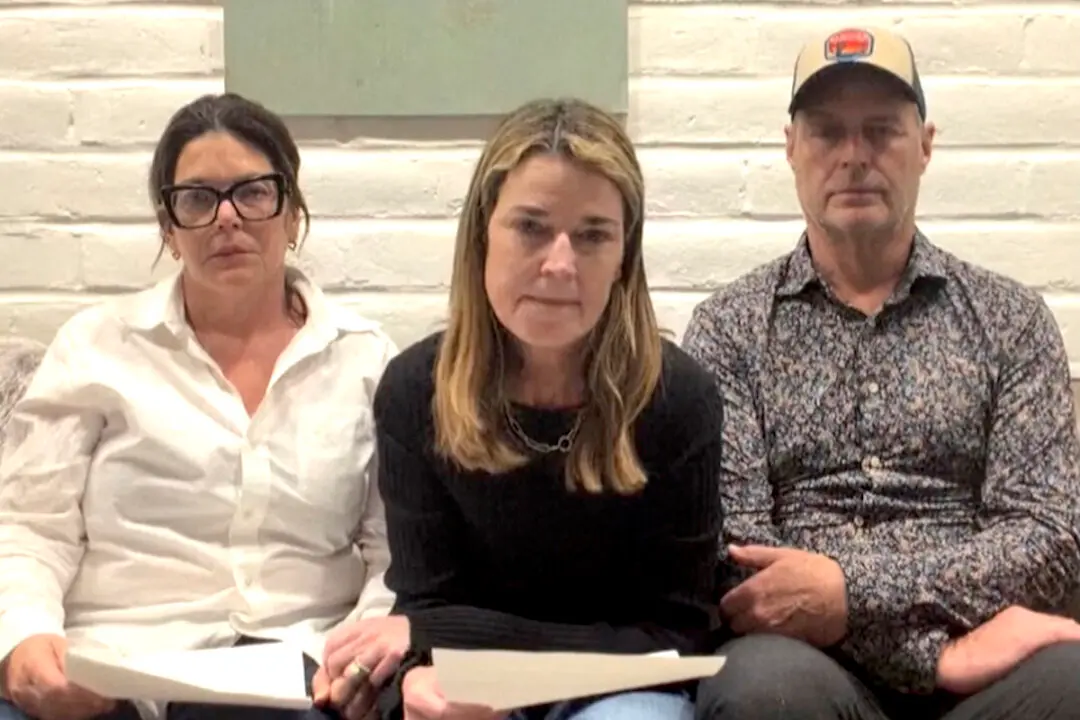

Many California landlords have been hit hard by statewide eviction moratoriums, allowing tenants to not pay rent for as long as three years. But now that moratoriums have been lifted across the state, evictions for some landlords are costing tens of thousands, forcing some to sell their property and leave the rental industry in California.

According to estimates by a landlord in Alameda County who led efforts to end the eviction moratoriums in Oakland, San Leandro, and in Alameda County—which lasted from March 2020 until the summer of 2023—there’s about $1 billion in unpaid back rent for Alameda County alone.