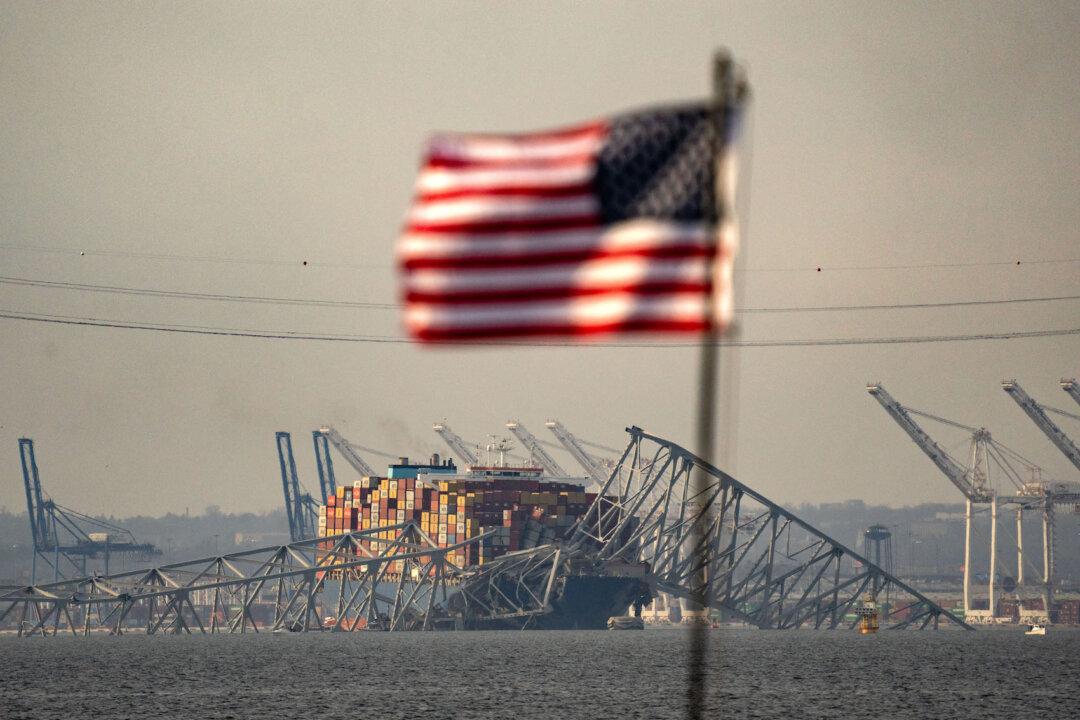

It took only moments for a three-football-field-long, 95,000-ton container carrier loaded with 262,000 tons of cargo to ram and knock down parts of the Francis Scott Bridge in Baltimore, but it could take years—decades—to sort out liabilities and award insurance claims.

In fact, according to Grady S. Hurley, a maritime attorney with New Orleans-based Jones Walker LLP, “it will be weeks, if not months” to merely ascertain the extent of damages, never mind determine who or what is at fault for the allision.