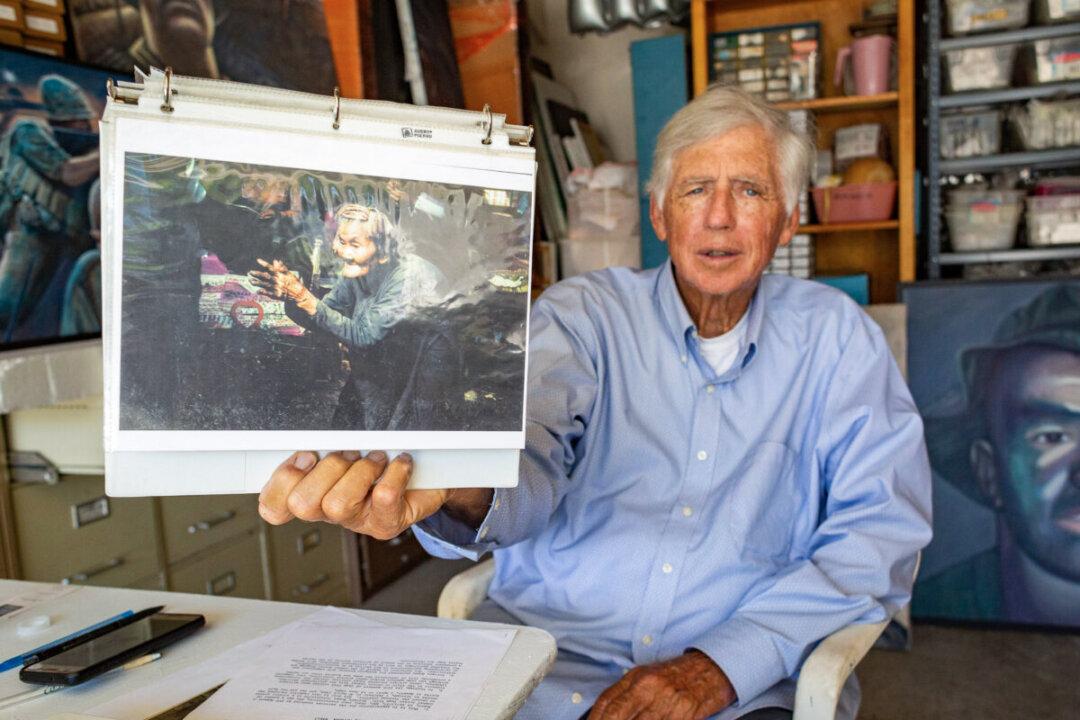

Don Schoendorfer’s perspective and faith took a 180-degree turn when a family member was diagnosed with bulimia in 1994.

An MIT-trained engineer by trade, he had encountered a problem in his life that he couldn’t fix with his technical knowledge. Up until that point, everything else—his job, finances, and relationships—was under control, Schoendorfer said. He believed in God and said he had finally encountered a problem only God could solve.