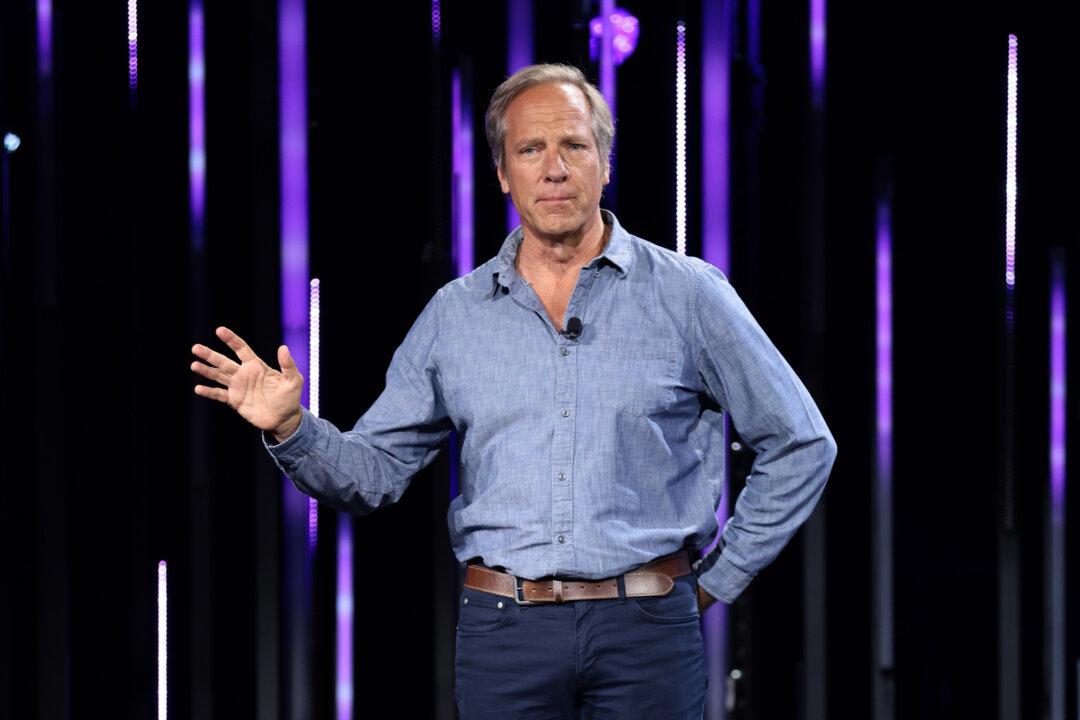

Mike Rowe has made a career by promoting the oft-overlooked jobs that keep society running via his hit TV series “Dirty Jobs.” But in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the low workforce participation rate has left many of those industries short-staffed.

“Right now, we have 7.2 million men, able-bodied men, in the prime of their working life, who are not only not working but affirmatively not looking. What they’re looking at are screens,” Mr. Rowe noted on the Nov. 23 episode of EpochTV’s “American Thought Leaders.”