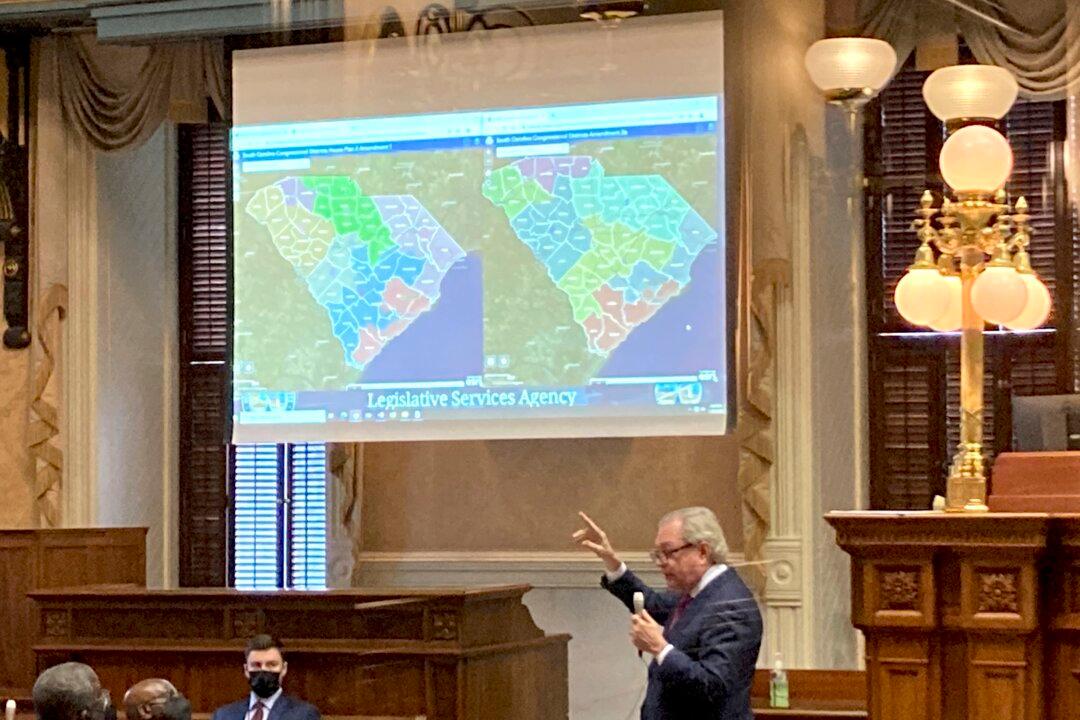

A three-judge panel ruled on March 28 that South Carolina must use a congressional map that the same court previously struck down for racial gerrymandering in the state’s upcoming elections.

The map, drawn by South Carolina’s Republican-controlled Legislature, bolsters the GOP’s advantage in the state’s First Congressional District—the seat currently held by Rep. Nancy Mace (R-S.C.).