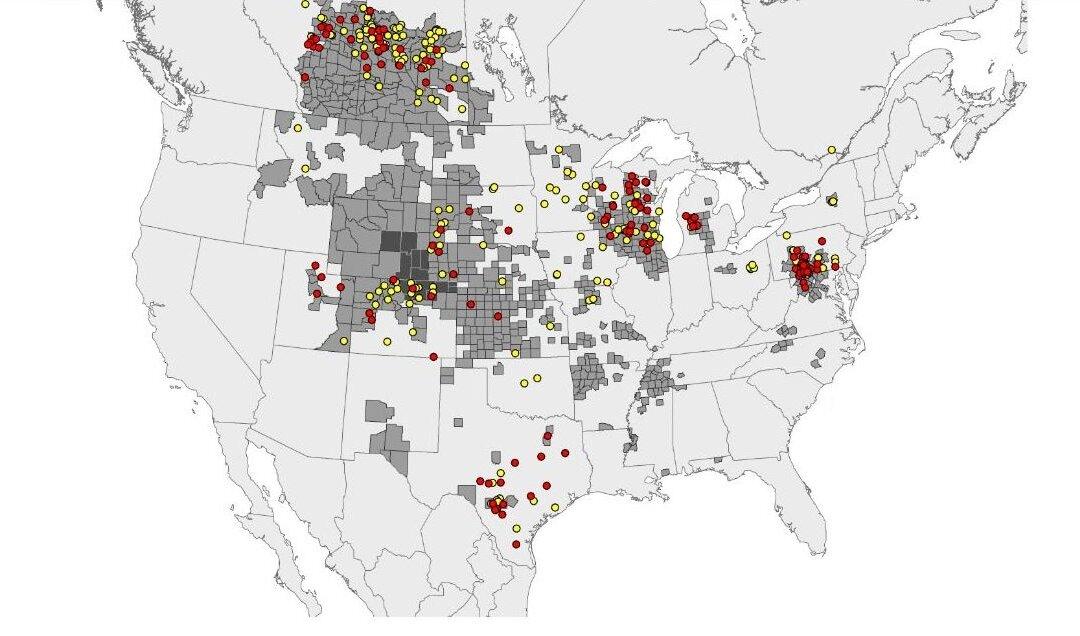

Some epidemiologists have expressed concerns that chronic wasting disease, sometimes called “zombie deer disease,” could be transmitted from deer to people as it spreads in wildlife populations near Yellowstone, triggering a new reaction from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Chronic wasting disease (CWD) primarily affects free-ranging deer, moose, and elk, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website. Officials have said there have been no infections among humans, although there have been sporadic warnings from researchers over the years about the disease possibly spreading to people.