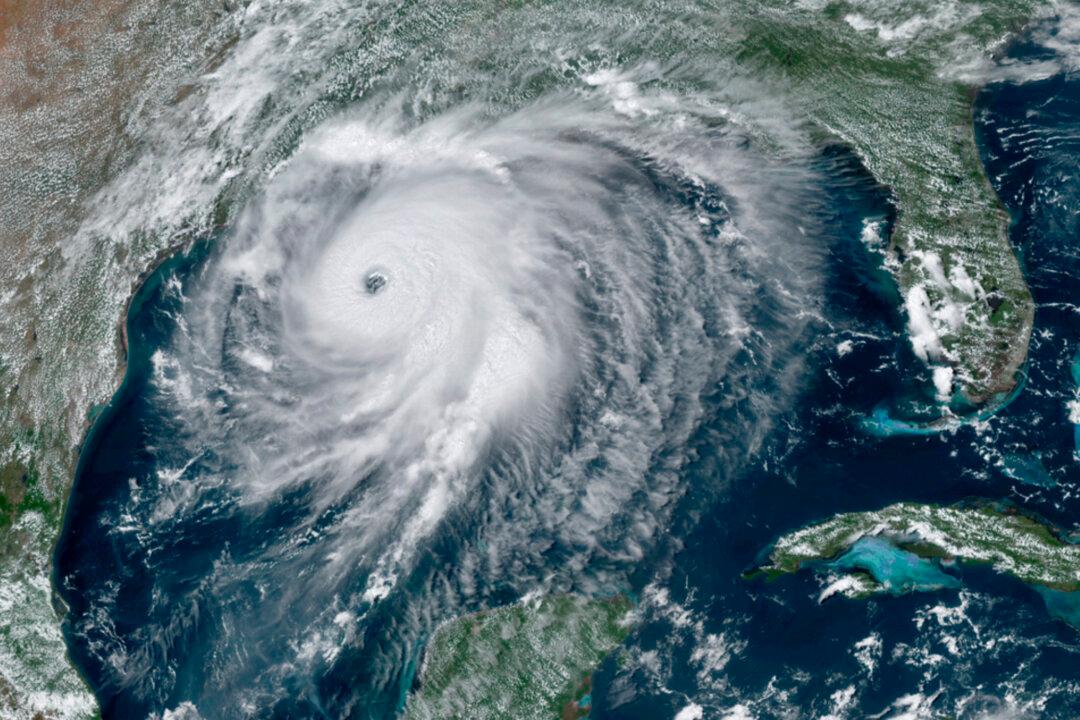

DELCAMBRE, La.—Laura roared toward landfall near the Lousiana-Texas border as a menacing Category 4 hurricane late Wednesday, raising fears of a 20-foot storm surge that forecasters said would be “unsurvivable” and capable of engulfing entire communities. Ocean water topped by white-capped waves began rising ominously as the monster neared.

Authorities implored coastal residents of Texas and Louisiana to evacuate, but not everyone did before winds began buffeting trees back and forth in an area that was devastated by Rita in 2005.