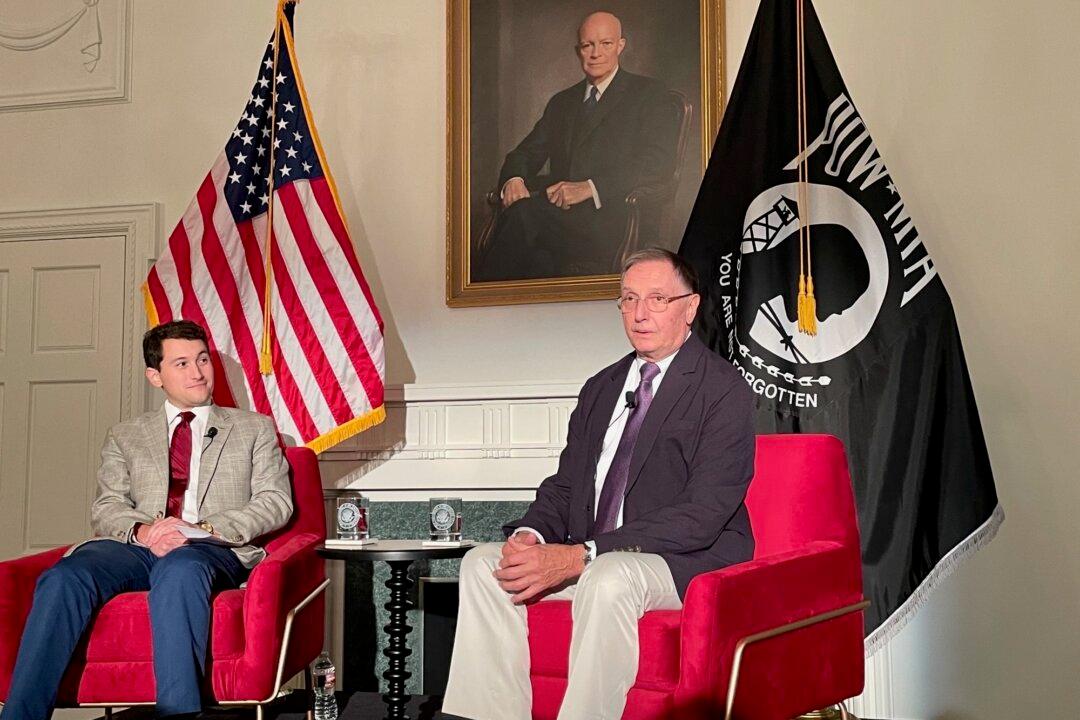

Air Force Lt. Colonel Tom Hanton had much to say to his small Yorba Linda, California, audience Aug. 29 as he recalled being shot down over North Vietnam in 1972.

Over 50 people came to hear Mr. Hanton’s story at the Nixon Library’s Cabinet Room, a talk which coincided with the museum’s 50 year anniversary marking when the last U.S. troops left Vietnam following the end of the war.