As some coastal towns in California are forced to build more housing while some rural areas face fewer demands from the state’s housing laws, some local leaders say they want to stop high density development from altering their suburban idyllic beach towns.

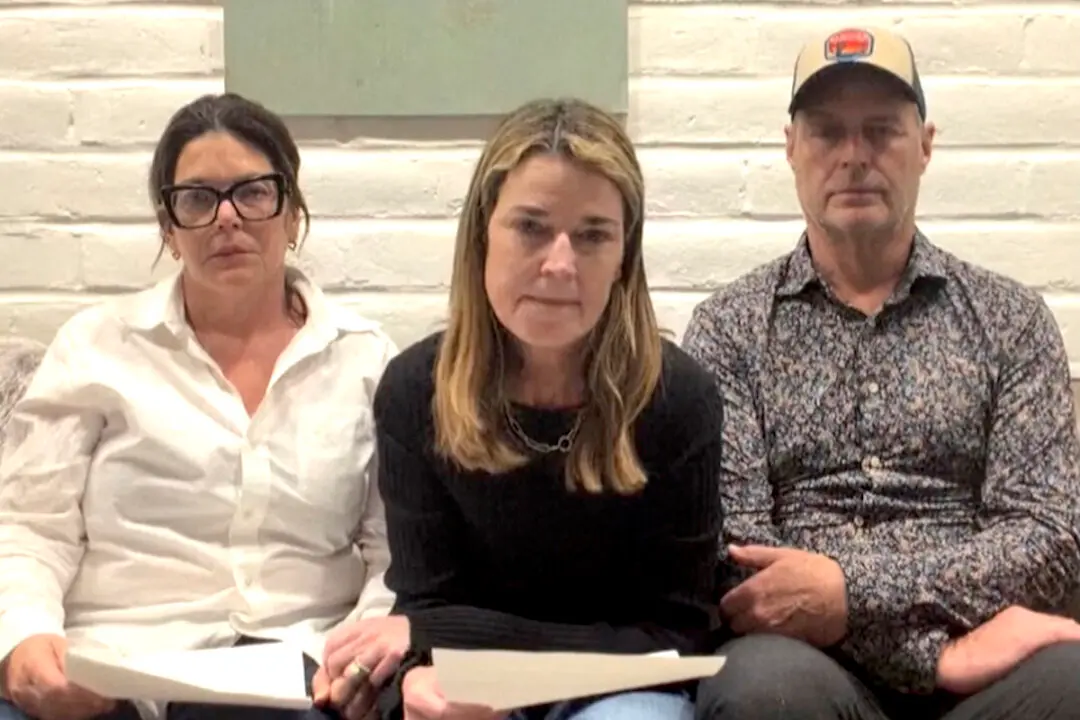

“The state’s basically coming in with these housing mandates and saying, hey, local city councils you can’t exercise the discretion that the voters vested you with, you have to make the decisions we tell you to make,” Huntington Beach City Attorney Michael Gates said on a recent episode of EpochTV’s California Insider.