When Vice President Kamala Harris visited Mexico last year, she cited poverty, crime, and political instability as “root causes” driving millions of migrants to cross the U.S. border.

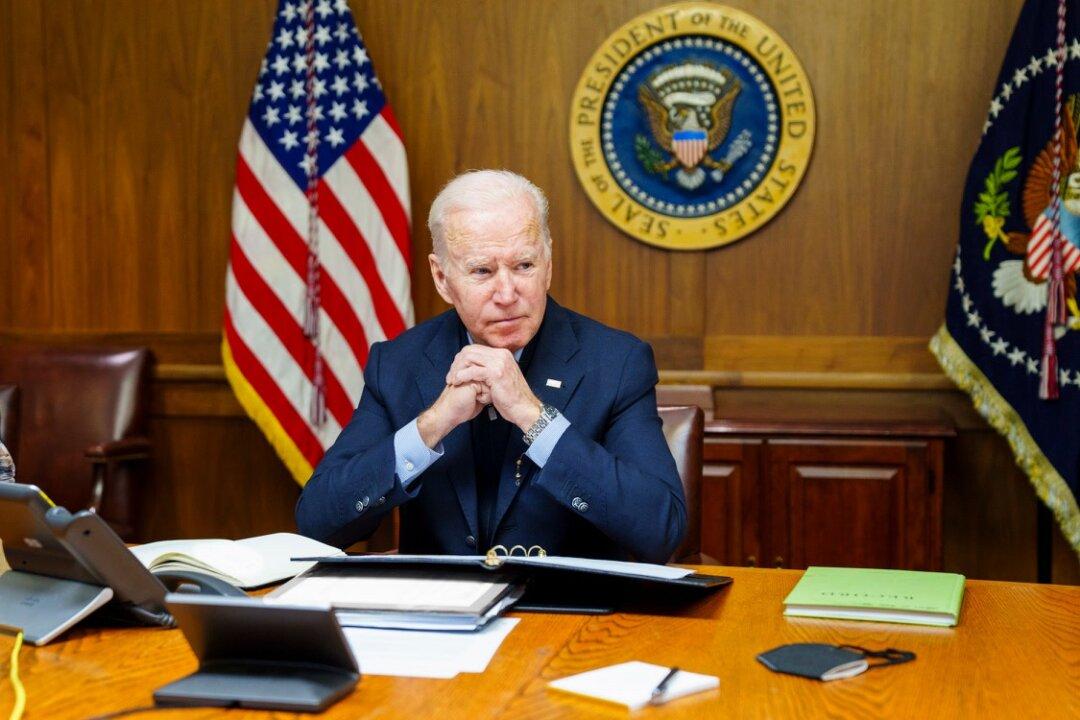

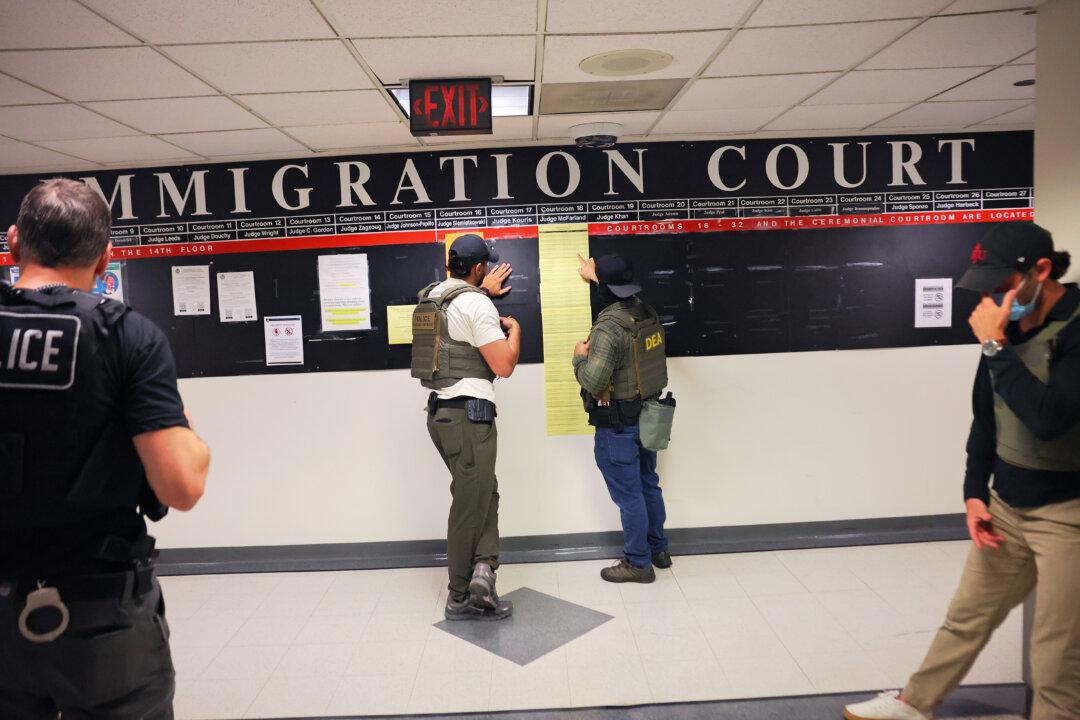

But some critics with regional expertise say Biden administration policies, which migrants have interpreted as an invitation to travel north, have severely worsened those root causes, destabilizing large swaths of Central America and Mexico. The torrent of people moving across the region has delivered billions of dollars to the coffers of human smuggling rings and the drug cartels that have taken advantage of America’s overwhelmed border patrol to deliver fentanyl and other deadly substances to the United States.