At critical moments over the past 25 years, The New York Times has aided the interests of a power faction within the Chinese Communist Party responsible for atrocities against practitioners of the spiritual discipline Falun Gong.

On top of implicating itself ethically, the paper has also, as a result, distorted its China coverage and misled its readers, as revealed by an analysis of The New York Times’ China coverage as well as interviews with half a dozen experts on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) politics and geopolitics.

Due to the paper’s disproportionate influence on policy, its skewed coverage has likely led to a loss of life and treasure that is difficult to quantify, some experts said.

The New York Times has for decades positioned itself as a global newspaper, insisting on the necessity of access to China, according to former staffers. That meant convincing the communist regime that the paper’s presence would benefit it.

The paper has never explained what price it has paid for access to the country.

“There’s always the issue of, if you want to be a global newspaper, what do you have to do to keep China happy and stay in business there?” Tom Kuntz, a former editor at the paper, told The Epoch Times.

“There’s always been tensions, and I know they’ve, like a lot of companies, tried to maintain access to China.”

Bradley Thayer, a former senior fellow at the Center for Security Policy, expert on strategic assessment of China, and a contributor to The Epoch Times, was more blunt.

“If they don’t cover the regime the way the regime wants to be covered, they’re going to be blackballed. They’re not going to be able to return,” he told The Epoch Times.

“So all of these individuals have a vested interest, if you will, in toeing the Party line.”

Covering Chinese politics, The New York Times has ascribed sincerity where deception is expected and glossed over where it should have dug deeper, all in a pattern of affinity with the interests of a CCP clique aligned with former Party leader Jiang Zemin, multiple experts affirmed.

Privileged Position

The paper developed a special connection with Jiang in 2001, when its then-publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., and several editors and reporters were granted a rare audience with the dictator.The paper ran an exclusive interview headlined “In Jiang’s Words: ‘I Hope the Western World Can Understand China Better.’”

Within days, the CCP unblocked access to The New York Times’ website in China.

A month later, the CCP unblocked several other Western news sites, including those of The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the BBC. The sites were blocked again within a week.

The interview came at a sensitive time for Jiang. He had only a little more than a year left before he was supposed to hand over Party control to Hu Jintao, fulfilling the succession line stipulated by Deng Xiaoping, his predecessor.

But things weren’t going well for Jiang. His persecution of the spiritual practice Falun Gong, a political campaign that was supposed to whip the Party and the nation into conformity under his control, was failing to reach its goals. Even worse, foreign media, including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post, were taking apart the CCP’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda and highlighting accounts of wrongful detention and torture.

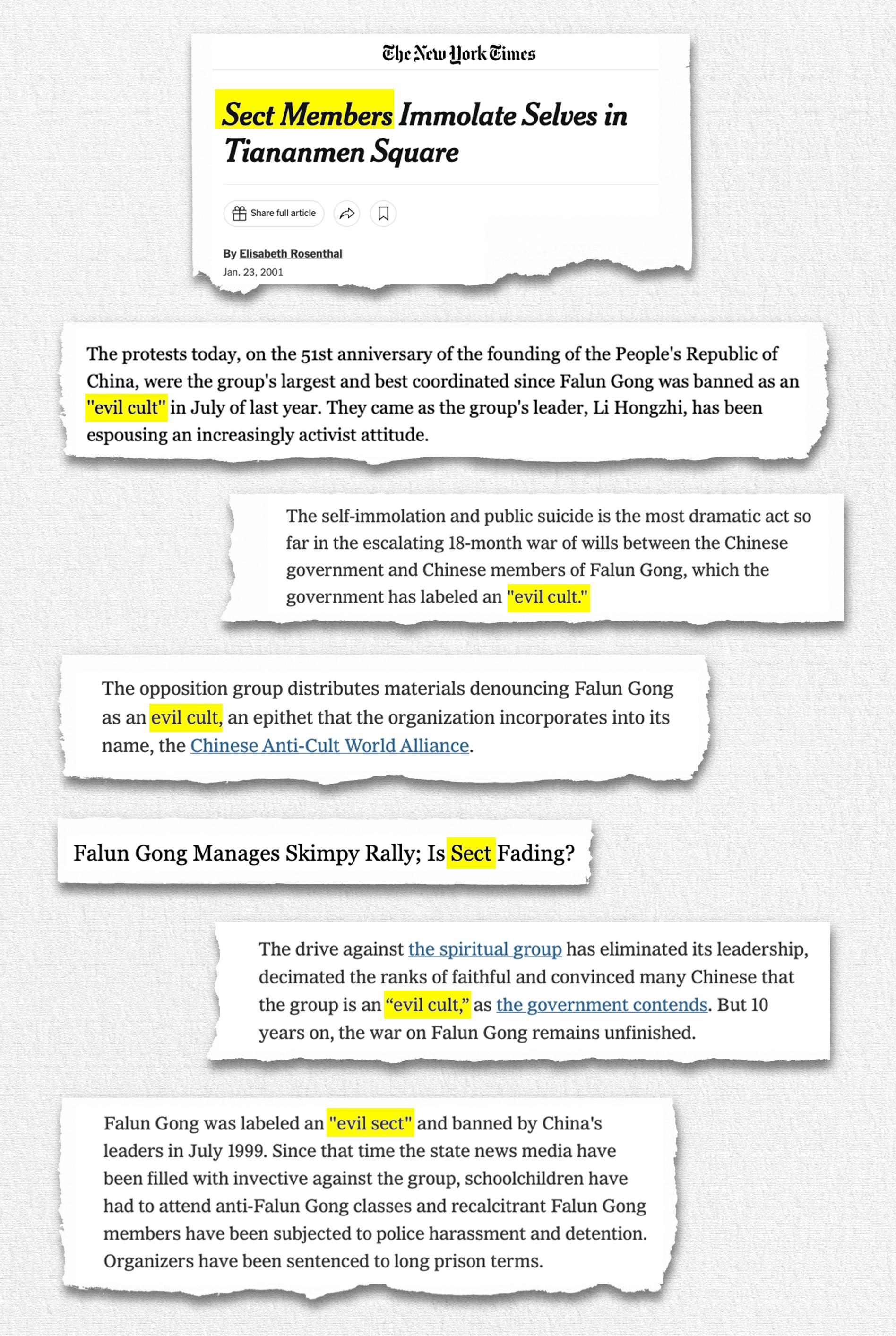

The New York Times, by contrast, appeared most helpful to Jiang’s campaign. By the time of the 2001 interview, the paper ran several dozen articles on Falun Gong, almost all of them repeating propaganda portraying the practice as a “cult” or a “sect.”

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a spiritual discipline consisting of slow-moving exercises and teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. It was introduced to the public in China in 1992, and by the end of the decade, an estimated 70 million to 100 million people were practicing it.

When in January 2001 CCP state media claimed that several people who set themselves on fire on Tiananmen Square in Beijing were Falun Gong practitioners, The Washington Post dispatched a reporter to fact-check the story. The New York Times, on the other hand, immediately took the CCP line as fact.

If the paper had employed its much-touted investigative acumen, it would have discovered, as others have, that the self-immolation incident was staged. After the first man allegedly set himself alight in the middle of the square, four policemen managed to obtain several fire extinguishers, rush to the scene, and put out the fire, all in under a minute.

Given the distances involved on the giant square, that wouldn’t have been physically possible—unless the officers already had the fire extinguishers ready and knew in advance where on the square they would be needed that day, several independent investigations concluded, pointing out dozens of other inconsistencies.

Even without any investigation, the incident made little sense. According to the CCP, the victims were supposedly following a belief that burning themselves alive would bring them to heaven. But Falun Gong includes no such belief; its literature treats suicide as killing a human life, which it explicitly prohibits. In fact, of the tens of millions of people practicing Falun Gong, none were said to have publicly set themselves on fire until that day, and none have done so since.

Even after The Washington Post investigation traced several of the alleged victims back to their hometown and found that none had ever been seen practicing Falun Gong, The New York Times continued to spread the CCP’s propaganda.

Jiang was apparently pleased with The New York Times, calling it “a very good paper” during the 2001 interview.

Shoring Up a Dictator’s Legacy

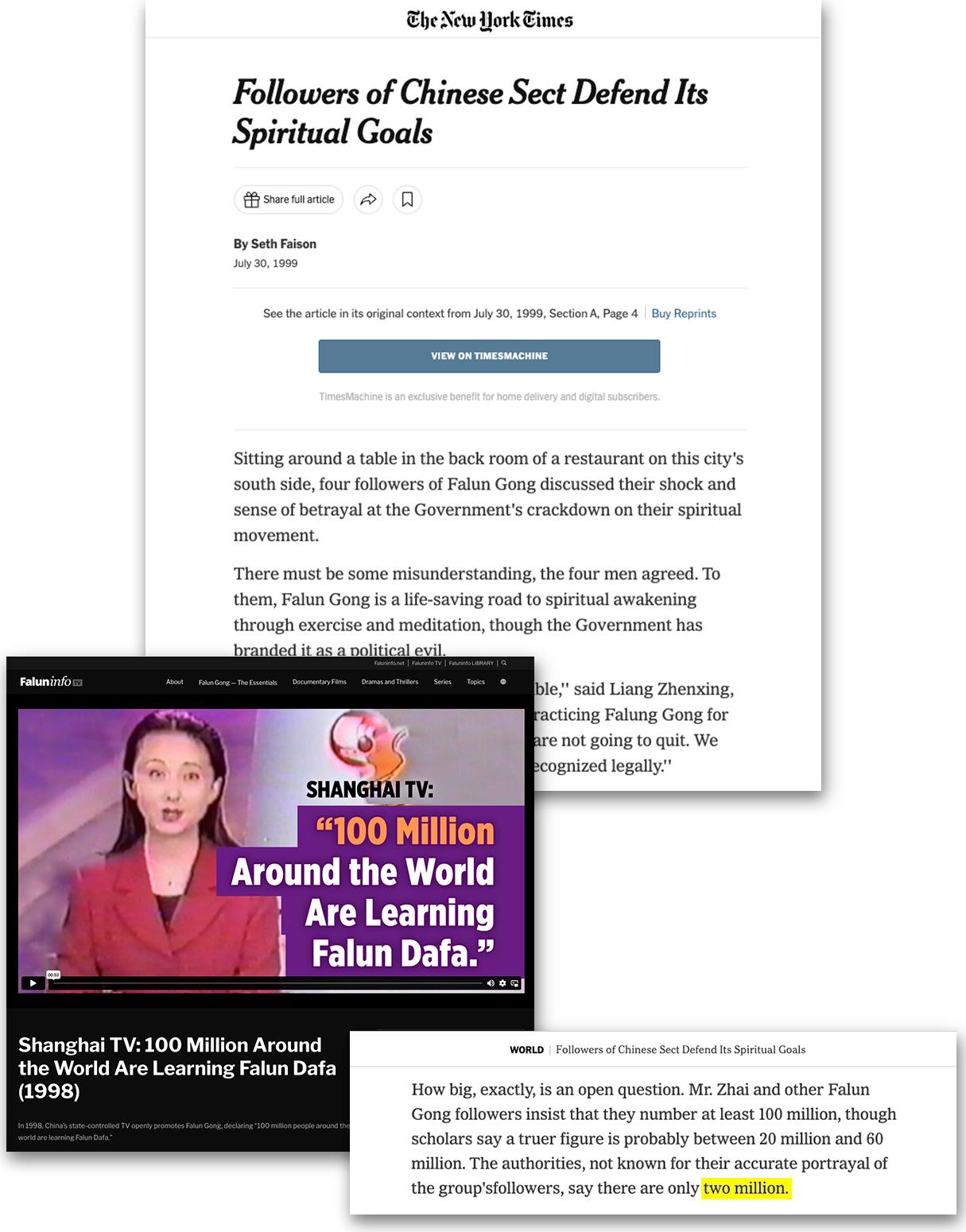

By 2002, The New York Times was in pro-Jiang mode. Citing CCP sources, the paper declared that Falun Gong had been successfully “crushed.” It suggested that Falun Gong was already passé and that it only ever had 2 million practitioners, going so far as to claim that the figure cited by Falun Gong sources, 100 million, was baseless.Yet a few years earlier, before the persecution began, multiple Western and Chinese media, including The Associated Press and The New York Times, provided figures of 70 million or 100 million, generally attributing them to estimates by the Chinese State Sports Administration, which had the best insight due to a massive survey of Falun Gong practitioners it conducted in the late 1990s.

Meanwhile, the paper was portraying Jiang’s legacy as one of a friendly reformer who ushered China onto the world stage.

“Mr. Jiang is, in Chinese terms, deeply pro-American,” declared a 2002 op-ed by one of the paper’s regular contributors.

Despite its past transgressions, China was “becoming more open, tolerant and important,” it said. Jiang’s decision to hold onto the top post in the CCP military past his 2002 retirement was portrayed by the paper as a somewhat controversial sign of strength.

Bloated Security State

In its coverage, The New York Times failed to catch the full significance of Jiang’s expansion of the Politburo Standing Committee, the body that officially rules the country, from seven to nine members. The move allowed him to add his propaganda chief, Li Changchun, as well as his head of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission (PLAC), Luo Gan.Under Jiang, the PLAC grew into an all-powerful behemoth controlling the entire national security apparatus. A major part of the reason was, again, the Falun Gong persecution campaign. Because Falun Gong was never officially outlawed in China, Jiang set up an extralegal police organization, called the 610 Office, to carry out the persecution. He put Luo in charge, giving him carte blanche to use whatever resources of the security apparatus needed to “eradicate” Falun Gong.

But Falun Gong was unlike any other group the regime had sought to crush. The usual tactics of rounding up leaders proved ineffective. Save for the practice’s founder, who was already exiled in the United States, Falun Gong lacked formal leaders or a hierarchy. Its local “coordinators” facilitated simple activities such as group exercises. When arrested, others easily picked up their roles.

As the persecution escalated, Falun Gong practitioners ceased to organize public activities in China and focused instead on “clarifying the truth”—explaining the facts about Falun Gong and the persecution individually from person to person. To disrupt their activities, the CCP’s security apparatus had to identify them, surveil them, and arrest them one by one—an immensely resource-intensive process.

The persecution required a massive expansion of the country’s police and surveillance apparatus, which was undertaken by Luo and his successor, Zhou Yongkang, who was also a close associate of Jiang, several analysts said.

China’s legal system, still in its infancy, was strangled in the cradle by the Falun Gong persecution, according to He Heng, a veteran China commentator with NTD, a sister outlet of The Epoch Times.

“They had to make an exception: Every established law must be [applied as if including] ‘except [for] Falun Gong,’” he said.

Typically, Falun Gong practitioners would be put on trial for “undermining the implementation of the law,” with the statute interpreted so broadly as to capture anything the regime found worthy of suppression, he said.

“The legal system got used to it. And they wouldn’t stop there. They would use this technique to extend their power to other people,” Heng said.

“That’s why China has never been able to establish a real legal system.”

None of this information graced the pages of The New York Times.

Sidelining of Bo Xilai

Bo Xilai was once considered a rising star of the CCP. One of the “princelings”—sons of early communist revolutionaries—he was groomed for CCP leadership. In 1993, he was appointed mayor of Dalian, a major port city in the northeastern Liaoning Province.According to Bo’s driver, who spilled the beans on his boss to a Chinese journalist, Bo was urged early on by Jiang to use the Falun Gong issue as a career ladder.

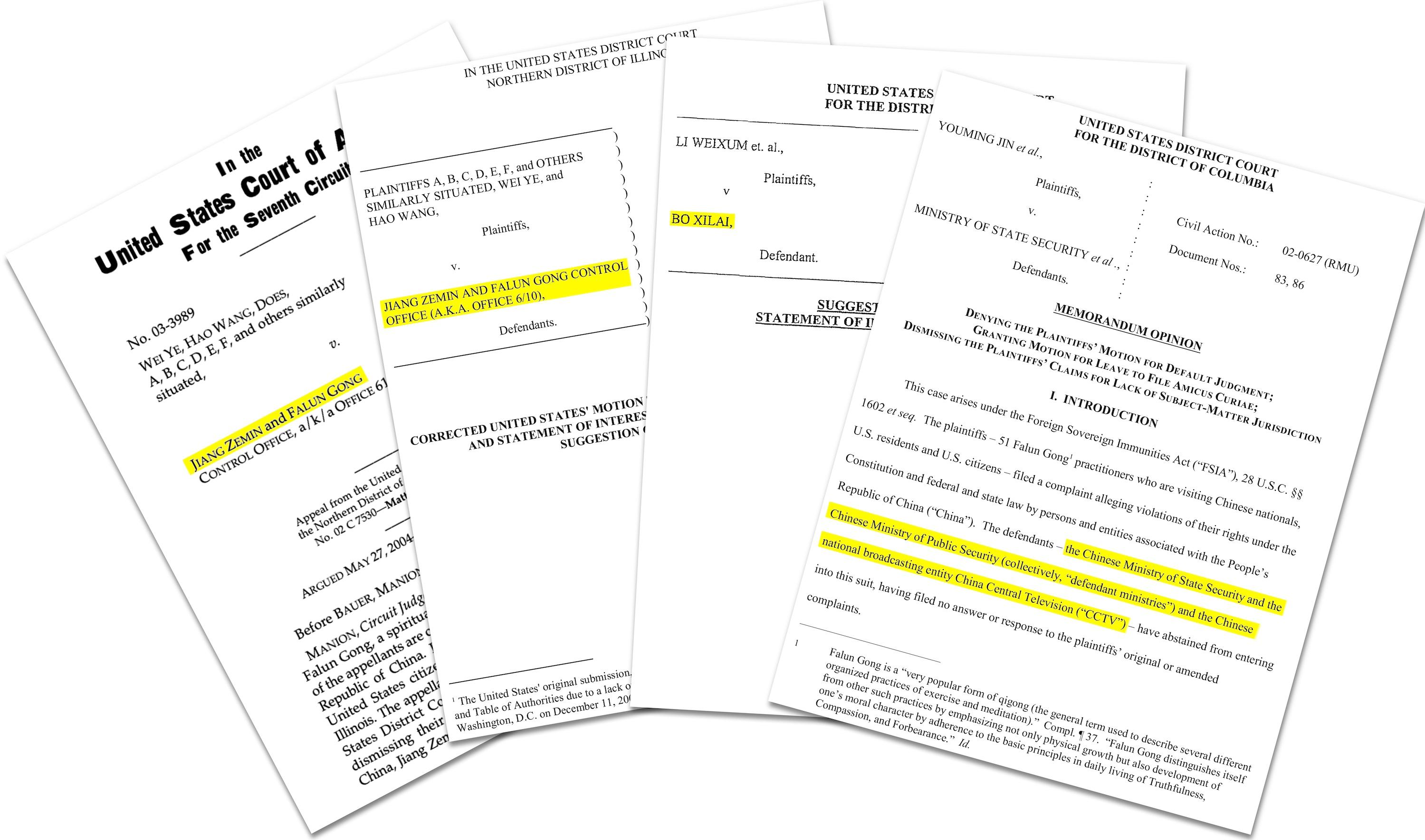

The New York Times never explored these issues, consistently ignoring Bo’s involvement in the persecution of Falun Gong. By 2009, Falun Gong practitioners had filed more than 70 lawsuits in more than 30 courts around the world against Jiang and other culprits in the persecution—a dozen of them against Bo.

Several U.S. courts granted default judgments against individuals personally involved in torture. In 2009, a Spanish court indicted five current and former CCP officials for torture, including Luo, Bo, and Jiang. That same year, an Argentinian court issued international arrest warrants for Jiang and Luo.

The article portrayed the judges as “overzealous” and “provocateurs.”

Killing for Organs

In 2006 the first information started to emerge from China about a new form of state-sponsored crime: killing prisoners of conscience for organs on demand.The case was blown open after overseas researchers started to call Chinese hospitals posing as patients or relatives of patients in need of transplants. In the recorded conversations, doctors openly confirmed that organs were available virtually on demand, within just a week or two. Some even affirmed that they could provide organs “from Falun Gong” when the investigators said they'd heard those were the healthiest.

Over the years, however, The New York Times has helped the CCP sweep the killing for organs issue under the rug.

In 2014, the CCP announced it would end the use of death row prisoners for transplants. When one New York Times reporter, Didi Kirsten Tatlow, received a lead that the practice hadn’t stopped and that prisoners of conscience were still being used, the paper blocked her investigation, she said. She left the paper shortly after.

Recently, when confronted with its record on the issue, a New York Times spokesperson told The Epoch Times that the paper did cover the issue of “forced organ donations” in China, referencing a single 2016 article by Tatlow that brought up the allegations but didn’t discuss the underlying evidence.

On Aug. 16, The New York Times published an article again ignoring the volume of evidence of the CCP’s practice of killing Falun Gong prisoners for organs. Instead, it relied on a single named China researcher, who said the evidence didn’t exist.

The Falun Dafa Information Center (FDIC), a nonprofit monitoring the persecution of Falun Gong, took issue with the expression “forced organ donation.” It was oxymoronic and “bizarre” to use “the words ‘forced’ and ‘donation’ in the same phrase,” FDIC said.

“The impact of the Times’ distorted reporting and irresponsible treatment of Falun Gong practitioners as ‘unworthy victims’ has contributed to the impunity enjoyed by perpetrators and robbed their victims of vital international support, undoubtedly resulting in greater suffering and loss of life throughout Mainland China,” it stated.

Safe Criticism

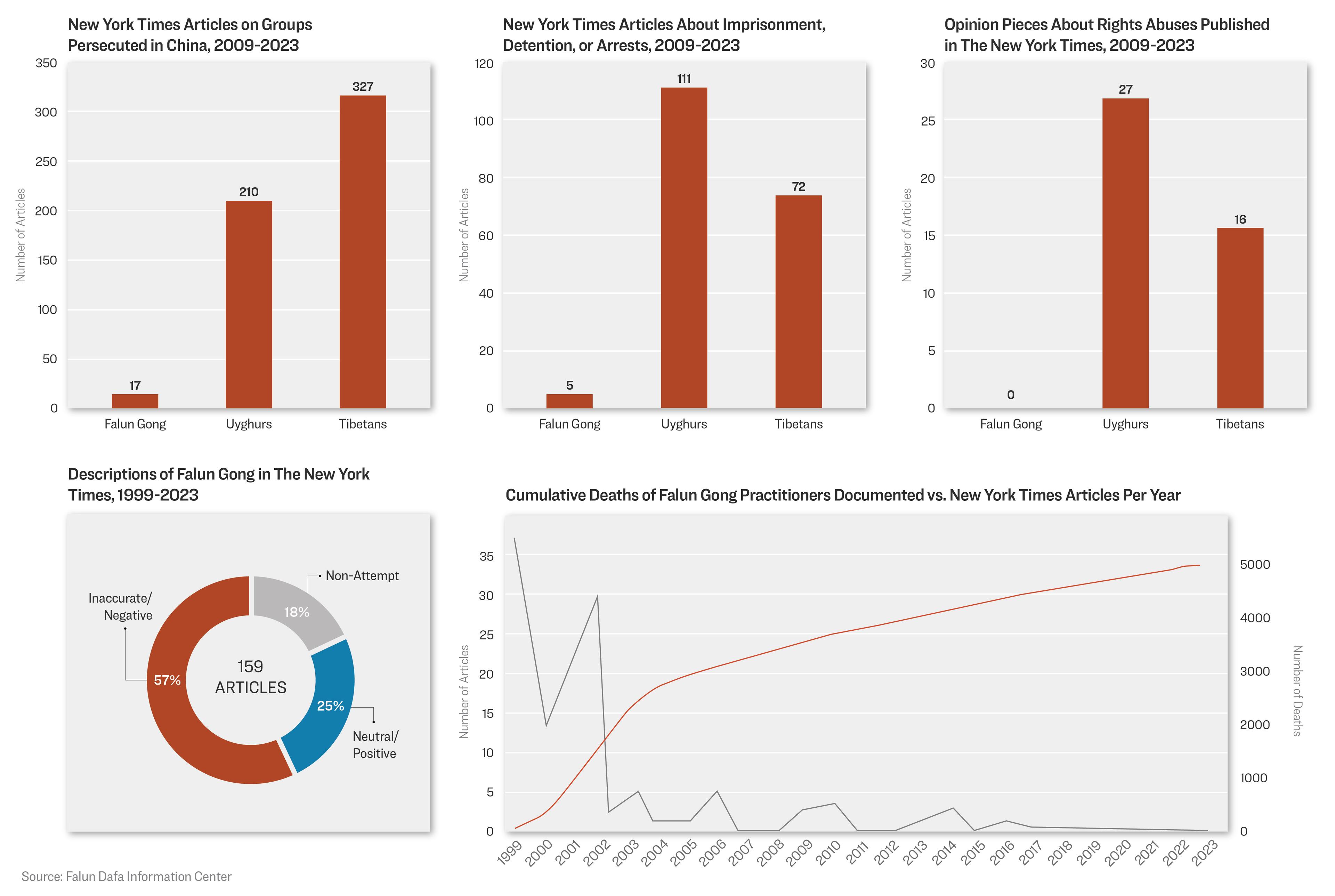

As the FDIC documented, between 2009 and 2023, the paper ran only 17 articles on Falun Gong, but more than 200 on the Uyghur issue and more than 300 on Tibet.From the perspective of the paper’s vested interests in China, criticizing human rights abuses in the far-away Tibet or Xinjiang was seen as relatively “safe,” according to Trevor Loudon, an expert on communist regimes and an Epoch Times contributor.

“That’s virtue signaling—‘See we stand for human rights.’ But they would never do that with Falun Gong because that would really offend the CCP. The CCP would throw a fit over that,” he told The Epoch Times.

While exposing abuses against Tibetans or Uyghurs sparks outrage overseas, it causes little instability domestically, Loudon said, because the ethnic minorities carry limited influence in China’s heartland.

Falun Gong, on the other hand, is “rooted in Chinese culture,” giving it an immediate appeal, he said.

“Chinese are not going to adopt Islam tomorrow. The Chinese are not going to adopt Tibetan Buddhism. But millions of Chinese have some sympathy for Falun Gong,” he said.

It’s also easier for the CCP to slap political labels on ethnic minorities—“separatists” on Tibetans and “terrorists” on Uyghurs.

Falun Gong practitioners, however, are mostly ordinary Chinese, scattered across the societal strata. Their only political demand has been for the regime to stop the persecution, Loudon said.

“The Chinese can’t say that Falun Gong are separatists. They can’t say they’re terrorists. They can’t say they’re political, really. All they can say is that they’re weird or crazy,” he said.

And that’s exactly the line of attack The New York Times aided, based on the FDIC report.

Engagement Doctrine

The United States was slow to respond to the CCP’s escalating aggression, and The New York Times proved less than helpful.“They know that they have to be intellectually honest at some level, but what they cannot do is ever connect the dots to talk about strategic trendlines,” James Fanell, a former naval intelligence officer and China expert who co-authored with Thayer the recent book “Embracing Communist China: America’s Greatest Strategic Failure,” told The Epoch Times.

The CCP intentionally kept its ultimate goals vague, presenting it as a “peaceful rise” of a “responsible” power. But the trajectory of the development wasn’t difficult to chart, the authors said.

Rather than a quest for emancipation, the Party’s goal of surpassing the United States economically and militarily reflects a pursuit of domination, they said.

The CCP’s talk about a “peaceful rise” and a “multipolar” world, where the United States, China, and other nations would share responsibility for maintaining order, amounts to little more than “smoke and chaff,” Fanell said.

“They know there’s only going to be one top dog,” he said. “They want to be the top power in the world. They’ve said that in many, many ways.”

Upstaging the United States as the leading world power would give the CCP the ability to dictate political and trade rules globally, the authors said. Pax Americana, for all its faults, has allowed for a measure of universal values, press freedom, religious freedom, and economic freedom. Pax Sinica under the CCP promises no such generosity, they warned.

“We know what it’s going to look like,” Fanell said. “We see it every day in China. Total control. Social credit system. State control of every facet of your life. That’s what it is.”

There’s no disabusing the CCP of its hegemonic ambitions, Thayer said.

“Xi Jinping could die tomorrow. He could die this afternoon, and the individual who replaces him is not going to go back to the happy time,” he said.

“The individual who replaces him is going to maintain the same policies, the same aggression, because the individual, at the end of the day, is far less important than the ideology of communism and the fact that their power has grown. And that ideology wedded to power explains their increasingly aggressive behavior internationally.”

Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been significant bipartisan agreement in the United States that the CCP’s ambitions need to be met head on—a strategy Thayer and Fanell endorsed.

The New York Times, however, has discouraged treating the CCP as an enemy. Instead, it has argued for continued engagement.

The engagement policy, which hollowed America’s manufacturing base and helped to turn China into a daunting military adversary, “has yielded less than its proponents hoped and prophesied,” the board wrote. It argued, however, that a relationship with China “continues to deliver substantial economic benefits to the residents of both countries and to the rest of the world.”

Thayer called such a framing “appalling.”

He said the engagement doctrine has allowed the regime to pull through moments of crisis and has blocked efforts to bring about its collapse.

“What the engagers did was prevent us from getting rid of this odious regime,” he said.

Interests and Nostalgia

The New York Times’ adherence to the engagement doctrine might trace back to several sources.Thayer blamed the paper for “ideological obtuseness where they refuse to see the nature of communist regimes as they are.”

“They have no trouble at all when it comes to condemning odious regimes. It’s only communist odious regimes where they have an ideological blindness,” he said.

Fannell pointed out that The New York Times has a vested interest in avoiding confrontation with China because it wants to maintain access to its market.

“I think it’s that obvious,” he said.

After prolonged devotion to the engagement doctrine, it’s also difficult for its proponents to admit they were wrong, he said.

“They just seem to be so obsessed with looking for anything to support their thesis.”

There’s also a sense of longing among some for China under Jiang’s rule—a time when The New York Times was allowed to do business in China and even criticize the regime to some degree, as long as it aped the Party line, particularly on Falun Gong.

“We were privileged to live in China during a remarkably free and open period of time, to learn the language, make friends, find spouses, and some for a while could even own property,” said Ian Johnson, who won a Pulitzer in 2001 for an incisive series on the Falun Gong persecution for The Wall Street Journal.

Stockman tacitly admitted the supposed “brain trust for the country’s foreign policy establishment” was blindsided by developments in China, which “was turning into something they hadn’t expected” and caused them to lose “visibility, access and insight.”

But the supposed golden age of China’s openness was always an illusion, multiple experts said.

Jiang’s apparent invitation to capitalists, lauded on the pages of The New York Times, turned out to be a sleight of hand, according to Desmond Shum, a former Chinese tycoon.

“I concluded that the Party’s honeymoon with entrepreneurs ... was a little more than a Leninist tactic, born in the Bolshevik Revolution, to divide the enemy in order to annihilate it,” he wrote in his memoir “Red Roulette.”

“Alliances with businessmen were temporary as part of the Party’s goal of total societal control. Once we were no longer needed ... we, too, would become the enemy.”

“It’s not a surprise that the aperture was very wide and that the regime, the CCP, invited in and rewarded amply individuals who were interacting, because the regime wanted, if you will, to profit from them, to use them, to use their skills, to use their abilities, to use their connections so that a positive image of the [People’s Republic of China] was projected and ... knowledge transfer could occur,” Thayer said.

Doubling Down

Instead of confronting reality, it appears The New York Times has been trying to recreate the illusion of “warm relations” it previously benefited from.In an unusual move, the paper’s executive editor, Kahn, personally contributed to the article—the only time he had done so since taking the top job at the paper earlier that year.

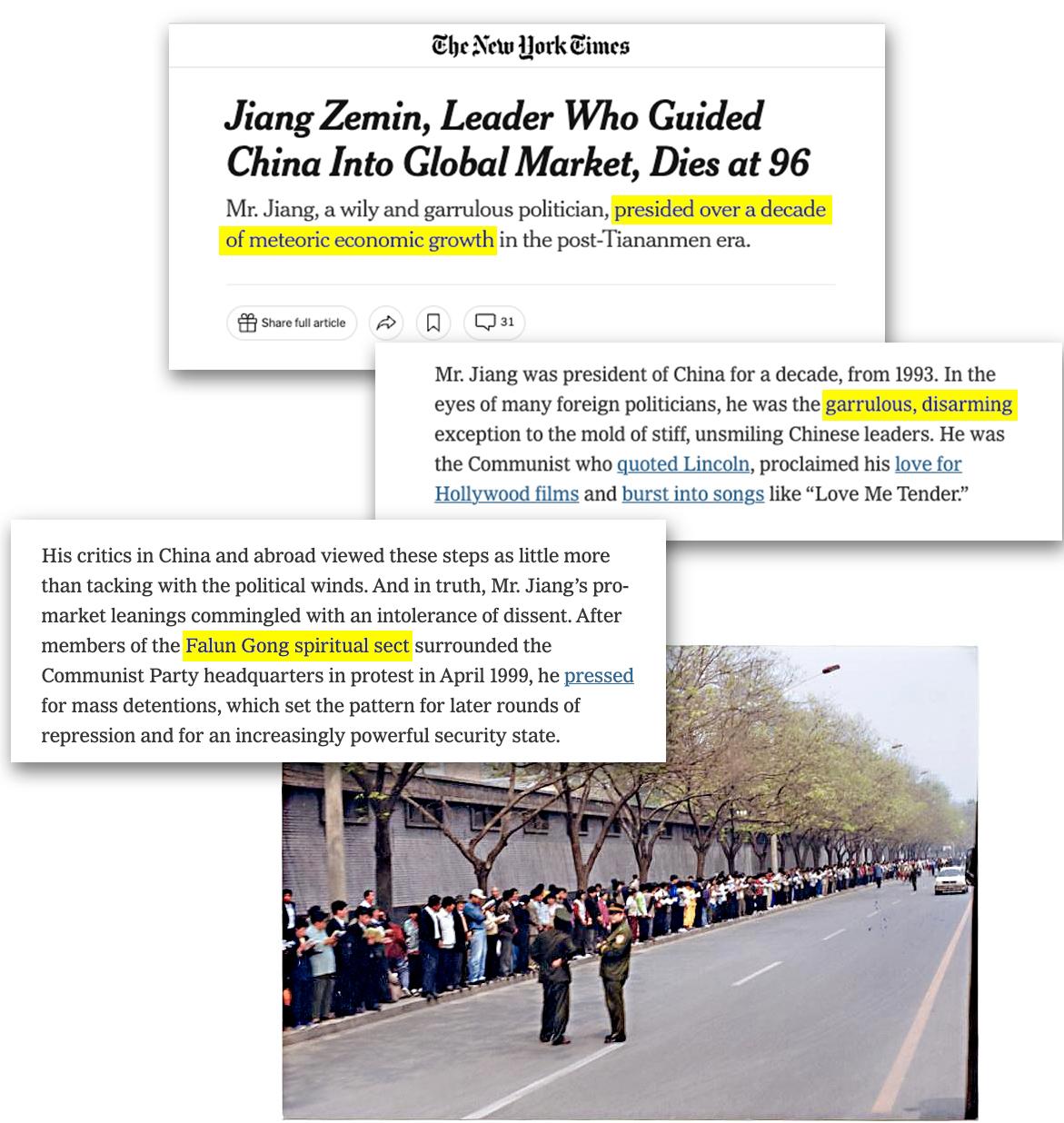

The nearly 3,000-word obituary represented an exercise in “willful ignorance,” whitewashing the communist dictator’s legacy of gore and deception, according to Thayer.

The article left out key aspects of Jiang’s story that “would allow him to be seen as the thug that he was,” he said.

Jiang’s responsibility for the persecution of Falun Gong was euphemized in the piece as mere “intolerance of dissent” and palmed off with a single sentence:

“After members of the Falun Gong spiritual sect surrounded the Communist Party headquarters in protest in April 1999, he pressed for mass detentions, which set the pattern for later rounds of repression and for an increasingly powerful security state.”

The dusting off of the “sect” label was significant, in the FDIC’s view. More than two decades ago, it implored the paper to drop it, not just because of the term’s pejorative implications, but also for technical inaccuracy. Falun Gong didn’t come up as an offshoot of another religion, but instead traced its origins to a practice transmitted along a private lineage, a similar trajectory to many practices that were popularized starting in the 1970s under the “qigong” moniker.

Yet somehow, this was par for the course at The New York Times, which has, since 2019, openly targeted the Falun Gong diaspora in the United States with a series of hit pieces that unearthed some of the worst excesses of its prior reporting, according to FDIC.

“Terms like ‘secretive’ or ‘dangerous’ repeat multiple times. ... Falun Gong beliefs are described as ‘extreme,’” the FDIC report reads.

CCP’s persecution of Falun Gong is usually glossed over in the articles as mere “accusations” or “claims tinged with hysteria,” it said.

The millions thrown in prisons and labor camps in China over the past quarter of a century suddenly became “tens of thousands ... in the early years of the crackdown.”

The distinction would have been easy to grasp for The New York Times. The Sulzberger family that leads it is Jewish, but that doesn’t mean the paper speaks for the religion of Judaism.

Despite all the paper’s efforts aligned with CCP interests, however, the CCP has shown little appreciation for The New York Times.

In February 2020, The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed by Walter Russell Mead headlined “China Is the Real Sick Man of Asia.” It panned China for mishandling the COVID-19 epidemic and questioned Beijing’s power and stability.

In late 2021, the Biden administration relaxed restrictions on Chinese media in the United States in exchange for the CCP giving The New York Times and others their visas back. But the CCP has been slow to do so. The paper seemed to have only two correspondents in China as of May 3.

There are indications, however, that The New York Times is doubling down. On Aug. 16, it ran a hit piece on Shen Yun Performing Arts, a massively popular classical Chinese dance company started by Falun Gong practitioners in the United States.

Shen Yun has been a prime target of the CCP, facing various forms of interference and sabotage. Its performances, under the tag line “China before communism,” seek to portray authentic Chinese culture. Some of its dance pieces also depict the persecution of Falun Gong.

It’s not clear whether the push against Shen Yun will win the paper more favorable treatment by the CCP.

“This is the nature of a communist regime. As they’ve grown in power, they’re going to start becoming a lot colder, they’re going to become a lot more repressive and treat foreigners, even individuals who used to be old friends of China, in a very different way,” Thayer said.

But The New York Times is already a willing partner in that effort, giving Xi little incentive to allow the paper a longer leash, Fanell and Thayer agreed.

“Xi Jinping doesn’t give a rat about The New York Times. He knows where they’re coming from,” Fanell said.

“He doesn’t even have to pay them off.”