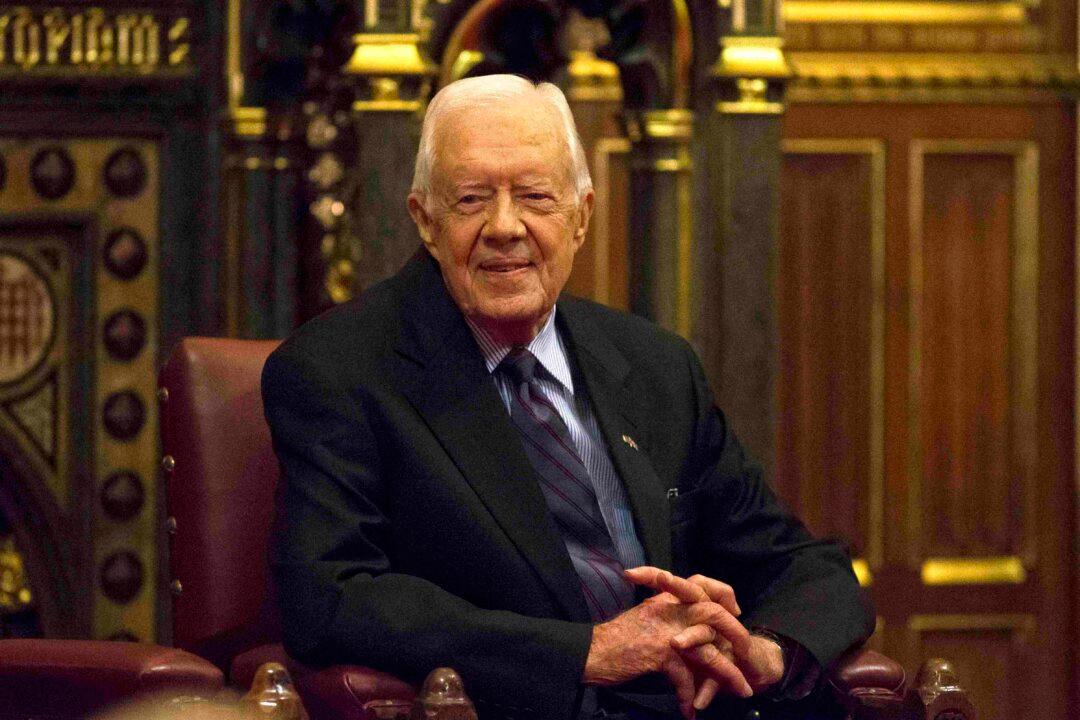

Former President Jimmy Carter died at his home in Plains, Georgia, on Dec. 29, at the age of 100. His life spanned a career of public service, including a single term as president from 1977 to 1981.

While Carter continued to build on a legacy of humanitarian work after leaving public office, his presidential term was marked by efforts to deal with inflation and a domestic energy crisis. On the international front, the 39th U.S. president sought to expand diplomacy with Russia and China and to advance peace in the Middle East.