Faced with a mounting roster of more than 3,200 exonerated Americans, some states, including Ohio, are taking steps to prevent the innocent from languishing behind bars.

Now, after more than two years of work, an Ohio Supreme Court-appointed task force is recommending that state lawmakers create an innocence inquiry commission, as part of “a patchwork of improvements” needed to decrease the likelihood of wrongful convictions and to promptly vet claims of actual innocence—a process that can drag on for decades.

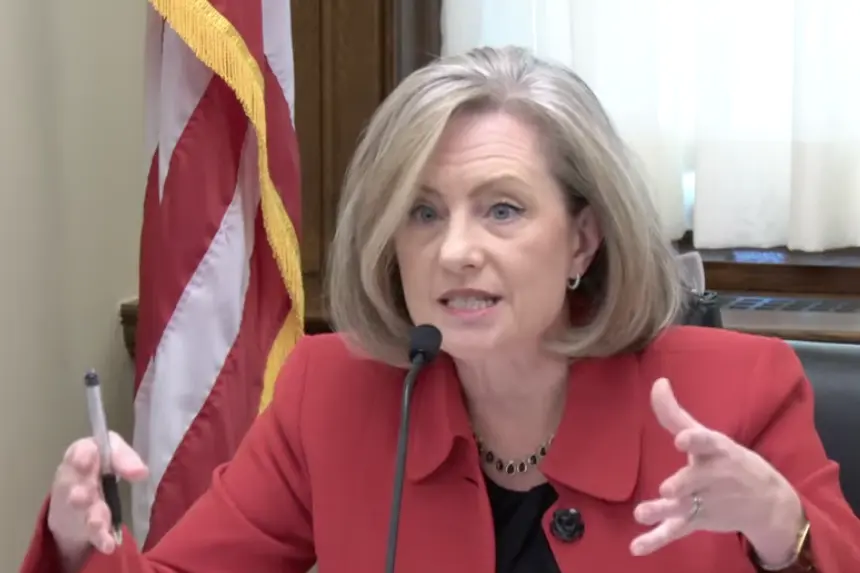

The recommendations were released on Aug. 15 in a report from the Task Force on Conviction Integrity and Postconviction Review. In 2020, Ohio Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor appointed the group of lawyers, judges, and other officials to study how the state handles claims of wrongful convictions and actual innocence.