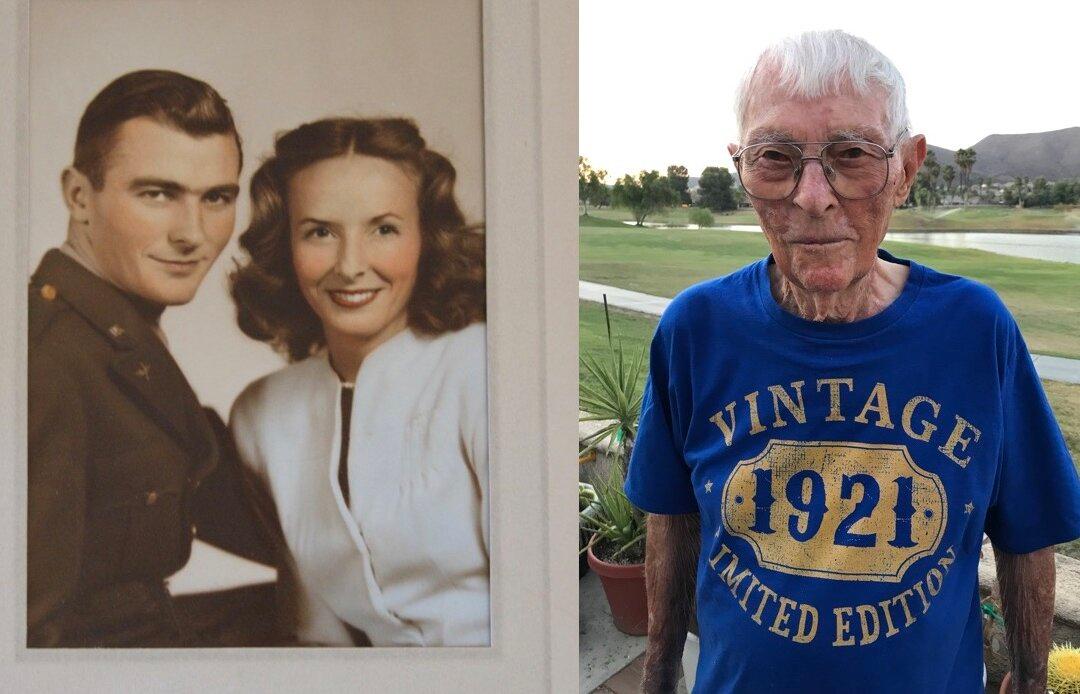

As a boy growing up in Southern California in the 1920s, Ed Reeder didn’t have a clue that his fascination with aviation would one day find him flying over occupied Germany with a Soviet fighter jet on his tail.

“That was scary as hell,” he said as he recalled the Russian fighter pilot that buzzed his Douglas C-47 Dakota transport plane during the Berlin Airlift in 1947 in the aftermath of the Second World War.