Last year was a bad one for the Chinese economy. Growth was slow, and the world was worried China would finally land the hard way, as many have been predicting for years. And more than GDP growth or any other metric, the Chinese currency was the barometer of whether China could keep things stable—stability is the mantra of the ruling communist regime—or suffer a crisis of debt deflation.

If it declined in value, it meant citizens and companies were moving money out of the country in droves because they didn’t believe in the Chinese dream anymore.

Trying to stem the tide, the central bank sold record amounts of foreign currency. Chinese foreign exchange reserves, $4 trillion at the peak in 2014, went down to $3 trillion, and analysts started to question whether this was enough to finance the world’s largest trading economy.

Weak Dollar

But something else helped China to strengthen its currency to reduce capital outflows and to balance foreign exchange reserves: a weak dollar.A weak dollar takes pressure off the yuan and makes it less desirable for Chinese to invest in U.S. assets if they stand to lose money on the currency. A weak dollar makes Chinese foreign currency holdings in other currencies worth more.

But the weak dollar is bound to reverse in 2018, and for China, this means going back to the uncertainty of 2016.

Currencies move for a myriad of reasons, but this year’s drop in the dollar had three major pillars. The first one was political.

After the dollar spiked 8 percent in the wake of the election of President Donald Trump last November, it dropped when it became clear Trump could not quickly push through his “America first” agenda, which included tax cuts and getting tough on trade with China and Mexico.

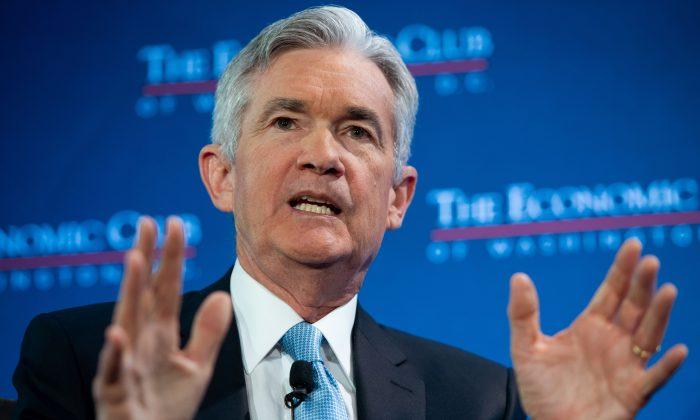

The second pillar was the interest policy of the Federal Reserve. The Fed always lagged behind its announced rate hiking schedule for 2016 and 2017, thereby disappointing market expectations of higher interest rates and a higher yield for the U.S. dollar.

Strong Dollar

All of these factors have changed in favor of the dollar in the last quarter, and it’s going to be hard for China to compete.Trump managed to deliver on key campaign promises in the last inning of 2017. The tax bill is a boon for national and international corporations, making it more competitive to invest in the United States again. It also incentivizes companies to bring back trillions in offshore money. Although this money likely won’t come from China, it will boost the dollar and indirectly punish the yuan.

China, on the other hand, has become ever less competitive both regarding taxes (the corporate rate is 45 percent) as well as cheaper wages. Its main advantage nowadays is scale. So according to a report by The Wall Street Journal, China is already preparing a contingency plan to counter the Trump reforms by raising interest rates, tightening capital controls, and micromanaging the currency by intervening in the foreign exchange markets.

Lower taxes for companies and individuals in the United States should also boost an already much-improved economy and therefore make U.S. assets like stocks and real estate more attractive for foreign buyers again.

But the United States is also threatening China on trade, whose $309 billion good trade surplus in 2017 provides powerful support for the yuan.

In late November, the United States filed a legal submission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) as a third party in a case China had brought against the European Union (EU) in late November. China is unhappy that, despite some WTO provisions, the EU has not granted it “market economy” status 15 years after joining. The United States rejects China’s arguments and sides with the EU.

If the administration follows through with its tough talk and uses the investigation into Chinese intellectual property theft under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to impose sanctions on China, a smaller trade surplus will hurt Chinese exports and the currency at the same time. Although a trade war will be costly for both sides, China has more to lose here.

If the administration follows through with its tough talk and uses the investigation into Chinese intellectual property theft under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to impose sanctions on China, a smaller trade surplus will hurt Chinese exports and the currency at the same time. Although a trade war will be costly for both sides, China has more to lose here.Independent of politics, the Fed is also starting to deliver on its interest rate hikes, making the dollar more attractive in international markets. It raised its benchmark policy rate 0.25 percent to 1.50 percent at its December meeting on Dec. 13.

The Chinese promptly followed suit, with the People’s Bank of China raising its benchmark rate by 0.05 percent to 3.25 percent. But research firm Capital Economics believes this won’t be a game changer and that financial conditions in China are still relatively loose.

“Despite this, we aren’t convinced by the narrative of policy tightening. A five basis point move in rates is too small to have a meaningful impact,” it writes in a note to clients.

However, if China doesn’t deliver on its reform schedule sooner than anticipated, it’s going to be 2016 all over again.