It’s the punch you don’t see coming—the boxer’s adage goes—that knocks you out.

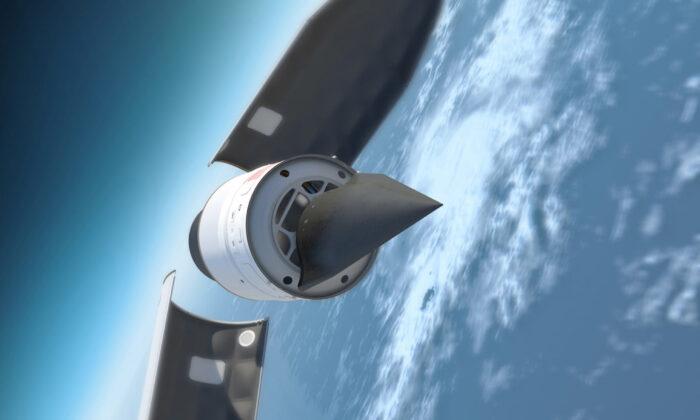

Hypersonic missiles are that latest military punch. Fast, yes. But more importantly, unpredictable, slipping past the digital eyes of military tech that watches for ballistic haymakers swinging out into space, not for glide vehicles skipping along the edge of the atmosphere.

They are the latest in a flurry of moves geared toward getting a variety of hypersonic weapons up and running within the next five years, as the United States scrambles to catch up with Russia and China.

Hypersonics are the latest missile tech, able to evade early detection by current ground radar and satellite systems, and maneuver with precision at speeds in excess of one mile per second.

The Trump administration wants hypersonics to help counter China and Russia’s long-range missiles and layers of defenses currently keeping aircraft and carriers at arm’s length.

Vladimir Putin wants them to bolster Russia’s nuclear posture.

And Beijing wants them to add to its nuclear options and the strategic headache for U.S. carrier commanders in the Pacific.

“The Chinese are very focused in this area,” said Timothy Walton, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

“They are the world leaders in terms of intermediate-range ballistic missiles and hypersonic weapons today,” he told The Epoch Times. “They’ve fielded a significant number of very long-range intermediate weapons. They’ve also fielded a hypersonic weapon that they’ve demonstrated and paraded last year, the DF-17.

“They have at least an initial hypersonic weapon capability in addition to scores if not hundreds of intermediate-range ballistic missiles that have a comparable capability.”

The Pentagon requested $2.6 billion last year (FY2020) for all hypersonic-related research. This year, it increased the budget request to $3.2 billion.

The Hypersonic Party Trick

Technically, “hypersonic” simply means something that goes more than five times the speed of sound. But the real party trick of hypersonics isn’t just speed.“The name is a little misleading. We actually already have missiles that can go that fast, or faster,” Patty-Jane Geller, a policy analyst in nuclear deterrence and missile defense at the Heritage Foundation, told The Epoch Times. “For example, the United States Minuteman ICBM goes Mach 23 during its descent.”

Those nuclear Minutemen are ballistic missiles. Like a rocket-powered Hail Mary pass, ballistic missiles are launched in a high arc, with momentum and gravity carrying them on a predictable path toward the target.

“Hypersonic missiles don’t follow the ballistic trajectory,” said Geller. “They cruise or fly to their target.”

In other words, she says, “they follow a flatter path that’s also lower in the sky.”

Rather than being launched hundreds of miles above the earth into space, hypersonics skip along the edge of the atmosphere, about 100 miles up.

“Cruise missiles and glide missiles usually don’t fly as fast as Mach 5. So that’s really the new capability—that we have these cruise and glide missiles going really fast.”

There are two broad categories of hypersonic missiles.

“The first is a hypersonic glide vehicle that is first launched from a rocket and then glides to its target,” Geller said. “The second is the hypersonic cruise missile that is powered by an air-breathing engine as it cruises to its target. [Both] these missiles are able to maneuver during flight, which makes their flight path unpredictable.”

Ballistic missiles can be spotted by sensors on the ground and high-orbit satellites when they are still rising in their trajectory, since it takes them high above the ground.

Doing China’s Homework for Them

Russia and China have recently developed hypersonic weapons that they claim are ready for use.At the end of 2019, Russia’s ministry of defense said it had put its first regiment of Mach 27 Avangard hypersonic missiles into service, as Putin claimed the West and other nations were “playing catch-up.”

He was right.

Hypersonic development goes back more than half a century, with the United States originally leading the pack.

“In past decades, we’ve been world leaders in hypersonic technology,” Mark Lewis, director of defense research and engineering for modernization at the Pentagon, told reporters on March 2. “But we have consistently made the decision to not transition that to weapon applications.”

While the United States paused hypersonics research at various points, Russia steadily continued its advances.

Both, however, were hampered by the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) treaty that restricted the development of both nuclear and conventional ground-launched, medium-range missiles.

China, in the meantime, was unbound by the INF treaty and has rapidly built up its hypersonics with huge investments in recent years, building on U.S. research that started in the 1940s.

Bolstering the US’s Negotiating Hand

The United States is now stomping on the gas to catch up, but unlike Russia and China, it doesn’t have any stated plans for putting nuclear warheads on hypersonics.Instead, it wants them to help dismantle the threat of China and Russia’s formidable array of missiles, amassed while the United States focused on counterinsurgency for 18 years.

Combined with improved anti-aircraft measures, those missiles have blunted the long-standing U.S. military supremacy, restraining once indomitable aircraft carriers.

Hypersonics are just one way that the United States is trying to solve this strategic puzzle, which is sometimes called the “anti-access denial” bubble.

Diplomatic Leverage

Beyond their military effect, mid-range hypersonics would give the United States “important diplomatic leverage” such as in future arms negotiations, Geller says.“For instance, the U.S. recently withdrew from the INF treaty because it caught Russia cheating. One of these missiles, the army’s hypersonic missile, would fit into the previously banned INF range.”

The nuclear arms treaty binding the United States and Russia–New START–expires at the end of this year. Trump administration officials have suggested that China should be brought into any future renegotiations.

“My issue right now is that China doesn’t seem interested in negotiating,” Geller says. “I think if we put missiles in the Pacific, particularly hypersonic, that might be something that would make them stop and think.”

Gearing Up for Large-Scale Production

But the table stakes for this particular geopolitical poker game are high. A midrange hypersonic glide weapon might cost between $10 million and $15 million per round, Walton says.Hypersonic cruise missiles could be significantly cheaper, he says. That’s because they would use a new type of air-breathing rocket engine that cuts back on fuel costs and weight.

Whilst Russia can unsettle adversaries with just a few nuclear-tipped hypersonic missiles, the United States is going to need many more, he says.

“Being able to acquire these weapons in operationally relevant numbers will be the most important factor in terms of their ability to contribute to campaign outcomes, and thus deter adversaries like China and Russia from engaging in aggressive actions,” Walton said.

The Pentagon is making a “major investment in the production of hypersonic weaponry at scale,” an official said on March 4, saying that the department was investing “many billions of dollars.”

One of the challenges for the United States is building up the industrial base, Walton says.

China, on the other hand, already has a “very mature defense industrial base that’s been focused in this area,” he said. “Many of the technologies that are required for intermediate-range ballistic missiles and the construction of the reentry vehicles are very similar to the same technology for hypersonic weapons.”

Another challenge for the United States is creating the precision needed to compensate for the weapon’s limited explosive power.

Keeping MAD

With Russia and China prepared to put nuclear warheads on hypersonics, some arms control analysts worry that it could destabilize the nuclear dynamic.But Geller and Walton don’t think it will much affect the dynamic much, which is still based on the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), not missile defense.

The MAD doctrine rests on nuclear nations having the ability to retaliate against a nuclear strike—the second-strike capability that, in the case of the United States, rests with its hidden nuclear submarines.

That deterrence is what currently safeguards the United States from nuclear attack, not its limited missile defense, Geller says.

“Currently, the United States does not have missile defenses capable of guarding against Russia and China’s full nuclear ICBM forces. Our defenses are limited to an accidental launch from North Korea or Iran. So having a different kind of weapon would have no new effect if we can’t defend against it anyway.”

However, Geller says that the maneuverability of hypersonics does change some of the nuclear considerations.

“If it’s a ballistic missile, we know if it’s going to hit a certain U.S. city, or some of our own forces. But we wouldn’t know that if it were a hypersonic. So that might change the thought process for a response.”

Some arms control experts have expressed concern that having both nuclear and conventional arms on another type of missile—known as dual-use—increases the chance of triggering a nuclear strike by accident.

But Walton says that this isn’t something new.

“The U.S. has, and China has a number of dual-use systems and they’ve had them for decades now—so that’s not new.

“That state of MAD likely will not change with the introduction of hypersonic weapons,” he said. “Depending on the launch profile of some of these weapons, they may be more difficult to detect using early warning ballistics missile systems.”

Walton points out that hypersonics are just one of a number of missile systems being developed by the United States to undo the strategic gains that China and Russia have made in the last decade or so.

Geller says that for now, “the jury’s still out” on whether hypersonics are the game-changing tech that some claim.

“They certainly present new problems for the U.S. military but I ultimately don’t think they will be a game-changing technology like, say, nuclear weapons.”