Conventional cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy, come with the drawback where they might also suppress or weaken our immune system by lowering the number of white blood cells and other immune system cells.

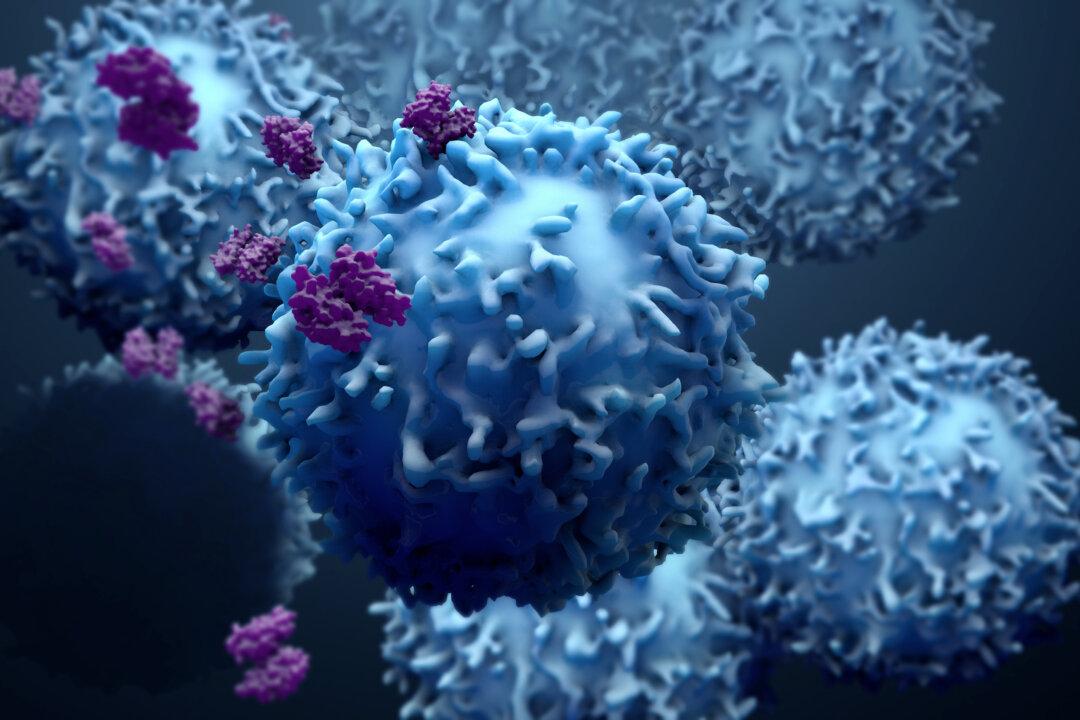

Immunotherapy is a relatively new type of cancer treatment that seeks to strengthen our immune system to fight cancer. But it is only effective in treating certain types of cancer.