Devon M. Herrick, Ph.D., is a health economist and expert on 21st-century medicine, including the evolution of Internet-based medicine, consumer-driven healthcare and key changes in the global health market. His research includes medical tourism, telemedicine, retail clinics, concierge medical practices, “shopping for drugs” strategies and value-based health plan design.

One of the more interesting aspects of his research is cosmetic medical services, one of the few areas of medicine where patients pay entirely out of pocket. As a result, patients act like consumers, and providers compete on price, quality, and other amenities. Unlike other areas of medicine, cosmetic medical prices are very stable, and the field behaves like a healthy marketplace.

The National Center for Policy Analysis (NCPA) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan public policy research organization. Their goal is to develop and promote private, free-market alternatives to government regulation and control, solving problems by relying on the strength of the competitive, entrepreneurial private sector.

SBB: What were you doing before you came to work at NCPA?

DMH: I began my career in healthcare accounting and financial management for a large healthcare system. I hold advanced degrees in business and finance.

Health economics was a way to incorporate what I knew from working as an accountant for a hospital and apply it to economics. Healthcare accounting is like getting stuck in the weeds, while health economics is a view of the whole system from 30,000 feet.

SSB: Why are pharmaceuticals in the United States so much more expensive than elsewhere?

DMH: There are several factors:

About 84 percent of drugs are paid for by someone other than the patient. This means that pharmacies and drug makers are geared up to maximize reimbursement from drug plans, employer plans, and insurers. If drug makers had to compete directly for consumers’ dollars, they would be much more competitive.

In many other countries, drugs are regulated and often reimbursed by local or provincial governments. These governmental organizations essentially set price ceilings (known as price controls in economics) to dictate prices. In a very real sense, these entities free-ride on research and development funded by Americans. Many drugs might not be developed without the prices paid by Americans. But since Americans are willing to pay more, other countries can demand price breaks that cover the marginal cost of production but not the cost of R&D. This is a form of price discrimination, where producers charge different prices in different markets.

Another reason why drugs are cheaper in other countries is many have a lower standard of living and drug makers know they cannot sell drugs to, say, poor Indians or those in Brazil, for the prices charged to U.S. customers.

SBB: Would you talk to readers about price controls?

DMH: It is against federal law to import a drug by anyone except the manufacturer. This is what allows drug makers to charge different prices in different countries. Some countries refuse to allow drug makers to set their own prices.

For the sake of argument, let’s assume a costly drug like Gilead’s Sovaldi is sold in India for something like $5,000 for an 84-pill course of treatment. The list price in the United States is $84,000. Why so much cheaper? Because most Indians cannot afford $84,000. But also, because India has refused to recognize Gilead’s patent.

As an implied threat to drug makers who won’t sell for a dictated price, some countries will use forced licensure. Gilead has also taken steps to prevent its cheap Sovaldi drug being sold in India to medical tourists (or suppliers) who might send it abroad where it would compete against more expensive versions of its drug.

Because of federal law, CVS, for example, cannot import cheaper licensed drugs from India or China without the manufacturer’s permission. That means there are fewer opportunities for Americans to import other countries’ price controls. That is how drug makers are able to charge different prices in different countries.

SBB: How do you see the situation changing so it’s more internationally competitive? Is there a better buying solution?

DMH: It’s actually getting worse.

Drug therapy is the best bargain in health care (only 10 percent of U.S. healthcare expenditures are on drugs). Among drug therapy, generic drugs are the best bargain; 88 percent of drugs dispensed in the United States are generic drugs, accounting for only 28 percent of drug spending.

Brand drugs comprise about 11 percent of drugs dispensed but account for nearly 40 percent of drug spending. By contrast, so-called specialty drugs—including biologics derived from living substances—comprise only 1 percent of drug therapies.

But these costly medications account for more than one-third of all drug spending. There is not a good path for generic competition among biologics (the term used is biosimilar). For example, it’s been years and there is still no form of cheap, generic insulin in the United States—although there is in other countries.

SBB: How does the media represent the drug-buying public?

DMH: The media has a tendency to be overly dramatic. Often, you hear about groups like Horizon Pharma, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, or Turing Pharmaceuticals. These are the bad actors that seem to hike prices. But the problem is one of economics: Firms are only responding to the incentives we give them.

If the FDA streamlined its approval process and was less risk averse, there would be more drug competition. Congress could also allow the FDA to use modern-day tools, such as more anecdotal evidence and Big Data trials. The approval process is unnecessarily rigid.

SBB: Other thoughts?

DMH: Americans need greater access to effective drug therapies. This includes moving more drugs over the counter where Americans can access them without a prescription. The FDA has gotten better about this, but lags behind many other countries.

One proposal is allowing oral contraceptives over the counter. Something some other countries do is have a third class of drugs known as “behind the counter.” These are drugs that a pharmacist can dispense without a doctor’s prescription. Examples include Zocor for high cholesterol in Britain. Also, Plan B in the United States is sold this way.

The trade association for OTC drug makers and some major retailers do not favor a behind the counter class of drugs. The reason is they are afraid a risk-averse FDA would make behind the counter the default class and stop moving drugs over-the-counter where they can be sold efficiently.

Once a drug becomes available as a generic, its price falls by 90 percent within a year if there are a number of competitors. Once that same drug is available OTC, the price is 95 percent to 99 percent cheaper than the prescription price.

SBB: Are we becoming overly reliant on drugs?

DMH: Some drugs aren’t efficacious and are only as effective as a placebo. Americans often engage in perverse lifestyle behaviors expecting a prescription drug to negate the negative effects. About 60 percent of medical expenditures are on diseases and conditions related to lifestyle. Much of the lipid-lowering drugs and drugs for hypertension could be thrown out if more Americans watched what they ate, followed a healthy diet, and exercised.

Too often Americans think pills are the cure for problems brought on by choices Americans have control over. Also, when Americans do need a prescription drug, they should understand the drug advertised on television is a costly drug. And, when given a free sample of a drug at the doctor’s office, Americans should know that drug is a costly drug not available in generic form. They should use the opportunity to ask their doctor if there is a similar drug available in generic form.

Drug makers often talk about the billions they invest in drug discovery and the high failure rate of new drug models. However, the process of drug discovery is made more difficult by bureaucracy at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA uses age-old methods to prove a drug is safe and effective. The agency is unnecessarily risk-averse in approving drugs.

About ten years ago, the FDA began an Unapproved Drug Initiative, where it actively sought to get old grandfathered drugs, safely used for decades, off the market. These were drugs that predated the approval process. Any firm willing to perform limited clinical trials on an old grandfathered drug could get market exclusivity for a period of years. By definition, market exclusivity jacks up the price. Also, if the FDA were allowed to use newer methods of assessing the efficacy of drugs, the process could be more streamlined, which could boost competition and lower prices.

SBB: Over the past few decades, drug makers have been accused of producing too many “me-too” follow-on drugs.

DMH: These were the competitors of first-in-class drugs. Drug makers had the goal of primarily developing new drugs that would treat large numbers of patients with chronic illness. There might be half a dozen cholesterol-lowering drugs, a dozen for hypertension, and so on.

The agency actively discouraged follow-on drugs. The FDA made it known that each successive application would have a higher bar for approval. As an economist, this makes no sense. These competitors to the first-in-class drugs are often better and lower the price through competition.

Instead, policymakers wanted drug companies to do research into rare diseases. If a disease is rare, drug companies have to charge a high price to make up for the low number of people taking the drugs.

As a result, instead of competition among common diseases, we have huge prices for new drugs for rare diseases. Spending on specialty drugs has about doubled in the past decade—now totally about one-third of all drug spending.

SBB: An example?

DMH: SSRIs are a growing class of medications. During roughly a two-decade period, use of antidepressants increased by nearly fourfold. Most of those taking antidepressants are not being cared for by a mental health professional; many merely get them from primary care providers. Some estimates put the proportion of middle-aged women on antidepressants at nearly one-quarter. Most other countries don’t use them to anywhere near the same degree.

Research suggests many SSRIs are about as effective as a placebo. It’s hard to say if depression is over-treated, or if the people receiving the pills are the ones who need them compared to others who need them and don’t receive them.

The topic is controversial. Americans have an international reputation as being workaholics. I’ve heard it suggested that Americans create stressful environments by feeling compelled to push themselves too hard, and stress is the result. Antidepressants could be stress relievers for people who burn the candle at both ends!

SBB: Thank you, Devon.

DMH: Thank you, Shelley.

Reflections: Creating an Industry That Bills You for the State of Your Health

Peter C. Gøtzsche, M.D., Danish medical researcher and leader of the Nordic Cochrane Center at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark, explains the problems with today’s pharmaceutical situation: “The main reason we take so many drugs is that drug companies don’t sell drugs, they sell lies about drugs. This is what makes drugs so different from anything else in life. … Virtually everything we know about drugs is what the companies have chosen to tell us and our doctors … the reason patients trust their medicine is that they extrapolate the trust they have in their doctors into the medicines they prescribe.

“If you don’t think the system is out of control, please email me and explain why drugs are the third leading cause of death. … If such a hugely lethal epidemic had been caused by a new bacterium or a virus, or even one-hundredth of it, we would have done everything we could to get it under control.”

The “illness business” makes more profit than any other industry on this planet. It makes more profit than the biochemical, automobile, and airline industries put together. And these profits are generated by a business need for universal ill heath.

One out of every four American citizens over 60 is taking prescribed medications. One in four American women in her 50s is taking antidepressants. The United States contains just five and a half percent of the planet’s population, yet it consumes more than half of all prescribed medication and 82 percent of the world’s intake of painkillers. Those who take prescription drugs take an average of four different prescriptions daily.

The prescribing of massive amounts of prescription drugs has created a medical disaster. A national industrialized bureaucratic burglarizing of what should be a nation’s healthcare reserves and its citizens’ taxpayer rights to healthcare. It is a nationalized plan to produce a profit from pain, while penalizing you for responsible healing.

People have become a market share in a merciless monetary industrial blueprint that is designed to keep humans both chronically unhealthy and dependent on, for the most part, an illusory and elusive nationalized Ponzi scheme that holds your health hostage to the pharmaceutical industry.

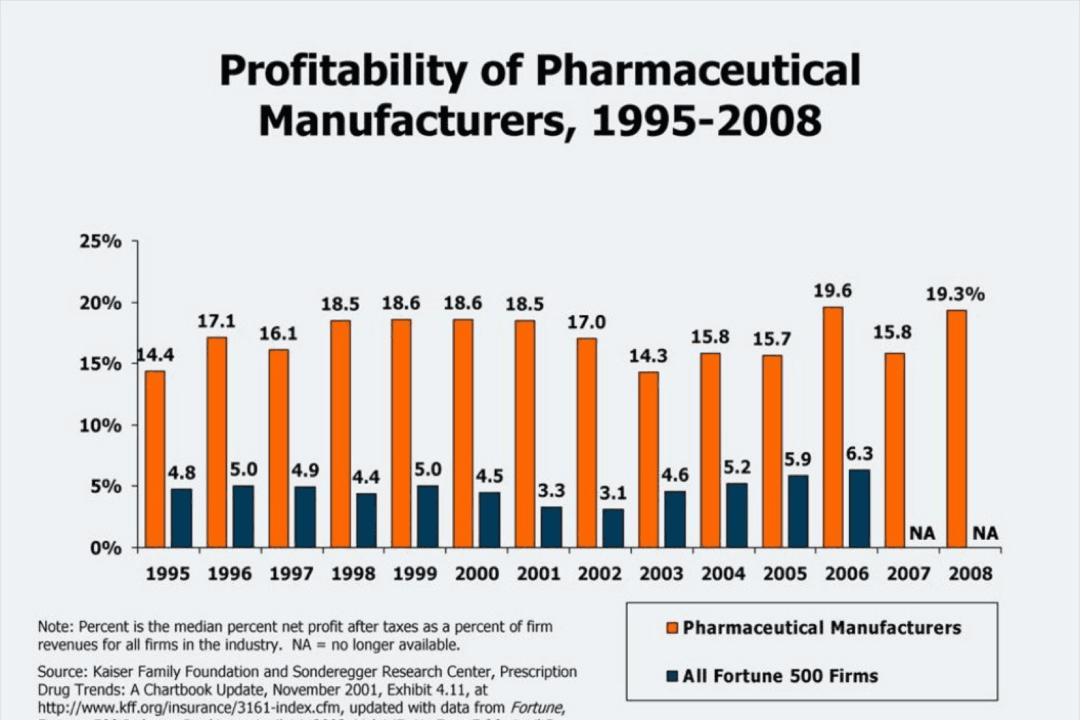

Six of the drug channel companies rank in the Fortune 500 list, while one manufacturer (Johnson & Johnson) made the top 50. The revenues of the eleven largest pharmaceutical manufacturers on the Fortune 500 list range from $74.3 billion (Johnson & Johnson) to $7.2 billion (Allergan). In March 2015, Actavis acquired Allergan. Since Actavis is based in Dublin, neither company will appear on the 2016 Fortune 500.

The top 10 pharmaceutical corporations generated, conservatively, in just one decade—2003 to 2012—net profits of three-quarters of a trillion dollars. The net profit for 2012 amounted to $85 billion in just that one year.

The majority of these largest pharmaceutical companies are headquartered in the United States, including the top four—Johnson & Johnson (#39 on Fortune 500 list), Pfizer (#51), Merck (#65), and Eli Lilly (#129), along with Abbott (#152) and Bristol-Myers Squibb (#176).

These businesses are structured, on every level, to profit from illness rather than wellness. Your health is being calculated, your wellbeing is being put at risk, and your wallet and financial security is headed for unnecessary, invasive surgery.

A wealthy nation’s healthcare infrastructure, its citizens’ healthcare rights and its taxpayers’ entitlements to modern healthcare are being held financial hostage by merchants whose interests are in marketing medications, rather than medical morality.

Shelley B. Blank has worked with major national and international newspapers as a journalist as well as a corporate executive. He has produced programs for Public Radio and lectured on modern multimedia communications and technology.